If you were selling computers in the early 1960s you faced a few problems, chief among them was convincing people to buy the fantastically expensive machines. But you also needed to develop an engineering force to build and maintain said machines. And in a world where most of the electrical engineers had cut their teeth on analog circuits built with vacuum tubes, that was no easy feat.

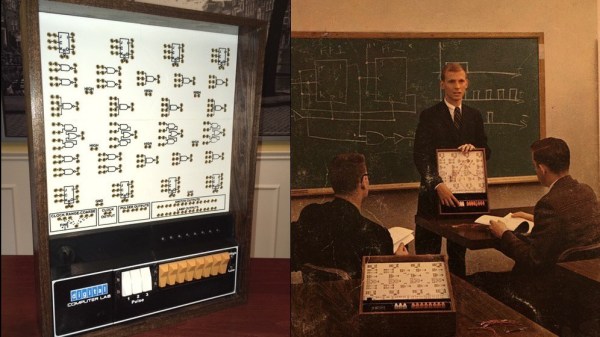

To ease the transition and develop some talent, Digital Equipment Corporation went all out with devices like the DEC H-500 Computer Lab, which retrocomputing wizard [Michael Gardi] is currently building a reproduction of. DEC’s idea was to provide a selection of logic gates, flip flops, and other elements of digital electronics that could be hooked together into more complicated circuits. We can practically see the young engineers in their white short-sleeve shirts and skinny ties laboring over the H-500 in a lab somewhere.

[Mike] is fortunate enough to have have access to an original H-500, but he wants anyone to be able to build one. His project page and the Instructables post go into great detail on how he made everything from the front panel to the banana plug jacks; almost everything in the build aside from the wood frame is custom 3D printed to mimic the original as much as possible. But the pièce de résistance is those delicious, butterscotch-colored DEC rocker switches. Taking some cues from custom switches he had previously built, he used reed switches and magnets to outfit the 3D printed rockers and make them look and feel like the originals. We can’t wait for the full PDP build.

Hats off to [Mike] for another stunning reproduction from the early years of the computer age. Be sure to check out his MiniVac 601 trainer, the Digi-Comp 1 mechanical computer, and the paperclip computer. If you’d like to pick [Mike’s] brain about this or any of his other incredible projects, he’ll be joining us for a Hack Chat in August.

Thanks to [Granzeier] for the tip!