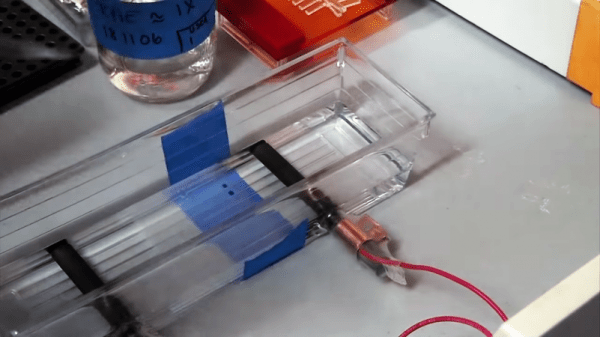

Back in the bad old days, dealing with DNA and RNA in a lab setting was often fraught with peril. Detection technologies were limited to radioisotopes and hideous chemicals like ethidium bromide, a cherry-red solution that was a fast track to cancer if accidentally ingested. It took time, patience, and plenty of training to use them, and even then, mistakes were commonplace.

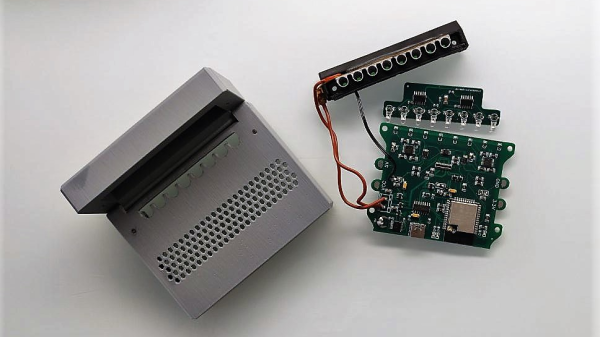

Luckily, things have progressed a lot since then, and fluorescence detection of nucleic acids has become much more common. The trouble is that the instruments needed to quantify these signals are priced out of the range of those who could benefit most from them. That’s why [Will Anderson] et al. came up with DIYNAFLUOR, an open-source nucleic acid fluorometer that can be built on a budget. The chemical principles behind fluorometry are simple — certain fluorescent dyes have the property of emitting much more light when they are bound to DNA or RNA than when they’re unbound, and that light can be measured easily. DIYNAFLUOR uses 3D-printed parts to hold a sample tube in an optical chamber that has a UV LED for excitation of the sample and a TLS2591 digital light sensor to read the emitted light. Optical bandpass filters clean up the excitation and emission spectra, and an Arduino runs the show.

The DIYNAFLUOR team put a lot of effort into making sure their instrument can get into as many hands as possible. First is the low BOM cost of around $40, which alone will open a lot of opportunities. They’ve also concentrated on making assembly as easy as possible, with a solder-optional design and printed parts that assemble with simple fasteners. The obvious target demographic for DIYNAFLUOR is STEM students, but the group also wants to see this used in austere settings such as field research and environmental monitoring. There’s a preprint available that shows results with commercial fluorescence nucleic acid detection kits, as well as detailing homebrew reagents that can be made in even modestly equipped labs.