What’s the difference between a 64k ROM in a 28-pin DIP and a 128k ROM in a 32-pin DIP? Aside from the obvious answers of “64k” and “four pins,” it turns out that these two chips have a lot in common, enough so that it only takes a little bodging to make them interchangeable — more or less.

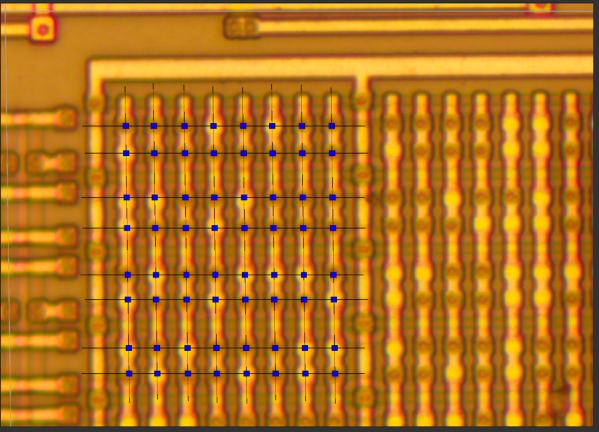

For a variety of reasons revealed in the video below, [Anders Nielsen] use the SST39SF010, a Flash ROM in a 32-pin DIP, in place of the old standby W27C512, an EEPROM in a 28-pin DIP. To deal with those pesky extra pins on the Flash ROM, [Anders] dug into the data sheets and found that thanks to JEDEC standards, almost everything about the pinouts of the two chips is identical. The only real difference is the location of Vcc, plus the presence of a 16th address bus line on the more capacious Flash ROM.

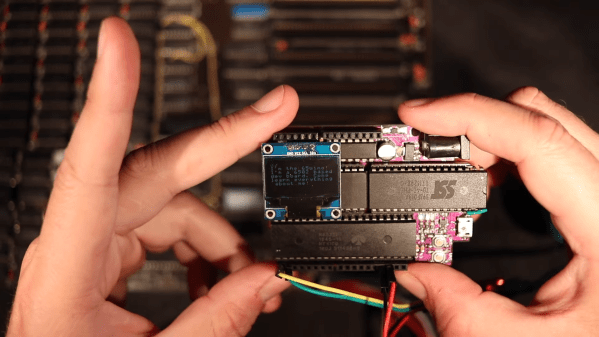

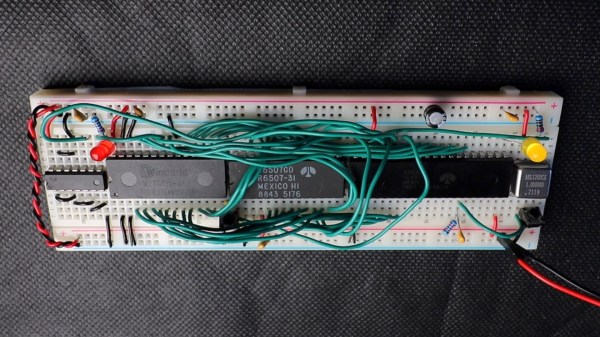

Willing to sacrifice the upper half of the Flash chip’s capacity, [Anders] set about bodging the 32-pin chip to work in a 28-pin socket. The mods include a jumper from pin 32 to pin 30 on the Flash chip, which puts Vcc in the right place, and adding a couple of pull-up resistors for write-enable and A16. Easy enough changes, but unfortunately, [Anders] chose a Flash ROM with heavily oxidized pins, leading to some cold solder joints and intermittent problems while testing. There’s also the fact that not all boards have room for overhanging pins, a problem solved by adding a socket to create a little vertical clearance.

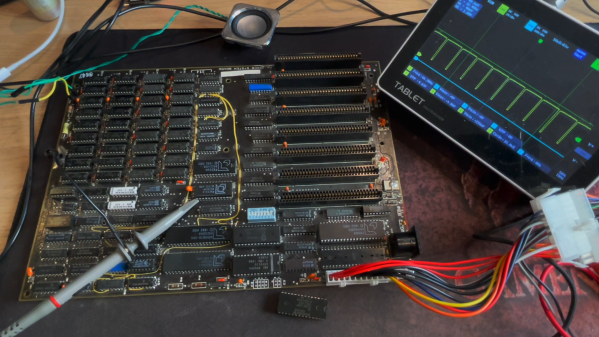

We found this to be a neat little hack, one that should make it a bit easier to use the wrong chip for the job. If you want to see where [Anders] is using these chips, check out his 6502 in an Arduino footprint or the bring-up of an old XT motherboard.

Continue reading “Stuffing A 32-Pin Chip Into A 28-Pin Socket”