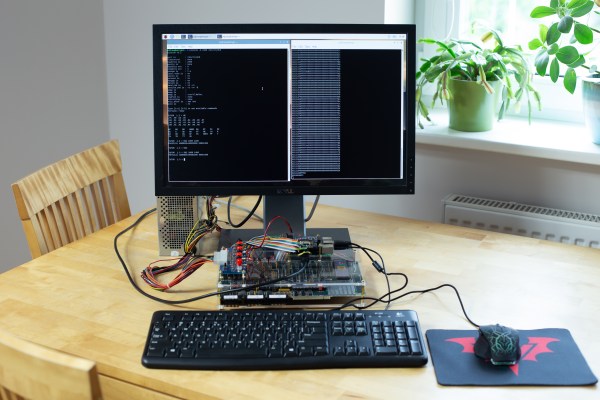

With Linux and the serial port there is good news and there is bad news. The good news is that Linux has great support for serial hardware of all sorts and a host of tools for accessing the serial port. That’s important when you use a lot of serial-like devices like Arduinos with USB ports and the like. The bad news is that most of the terminal software is made to accommodate the days when a computer had real serial terminals and modems with people interacting with them. We bet that’s why [lundmar] developed tio, a serial device I/O tool for people like us.

Honestly, how many times have you needed Zmodem file transfers and recognition of the DCD signal to detect an incoming connection? Sure there are many other programs that will do the job, but tio brings a clean simplicity along with functionality that embedded developers need.

The software will support arbitrary devices, show statistics, and give you control of the RS232 lines. There’s support for delayed characters and lines, useful if you are dealing with a super simple device with no handshaking. There’s also hex support and many ways to log data and statistics. We especially like that it can automatically reconnect which is a great feature.

Of course, you want some terminal features and tio includes those. For example, you can elect to have local echo turned on or map characters so that, for example, a carriage return turns into a carriage return and a line feed. You can use command line options to set up most items including features like redirecting to a network socket. Other commands inside the program — by default, triggered by Control+T — let you do things like send a break, toggle handshaking lines, and more.

You might think the serial port is dead, but it really just transformed into a USB port. Of course, like everything else these days, you can also get your terminal in the browser.