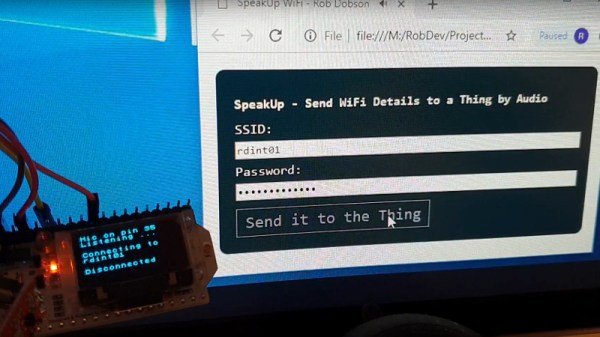

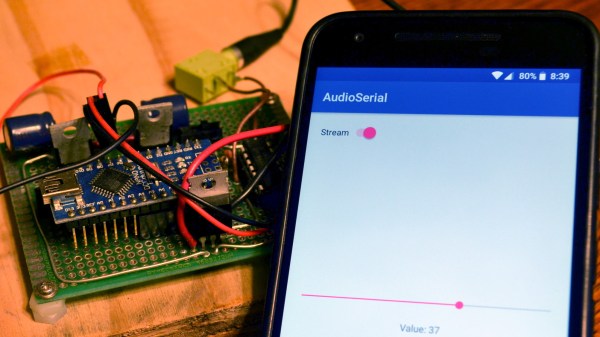

When you create a Thing for the Internet of Things, you’ve made a little computer that does a simple job and which probably has a minimal interface. But minimal interfaces leave little room for configuration, such as entering WiFi details. Perhaps if you made the Thing yourself you’ve hard-coded your WiFi credentials in your code, but that hardly translates to multiple instances. So, how to put end-user WiFi credentials easily on more than one Thing? Perhaps [Rob Dobson] has the answer with his technique of sending them as a sequence of audible tones.

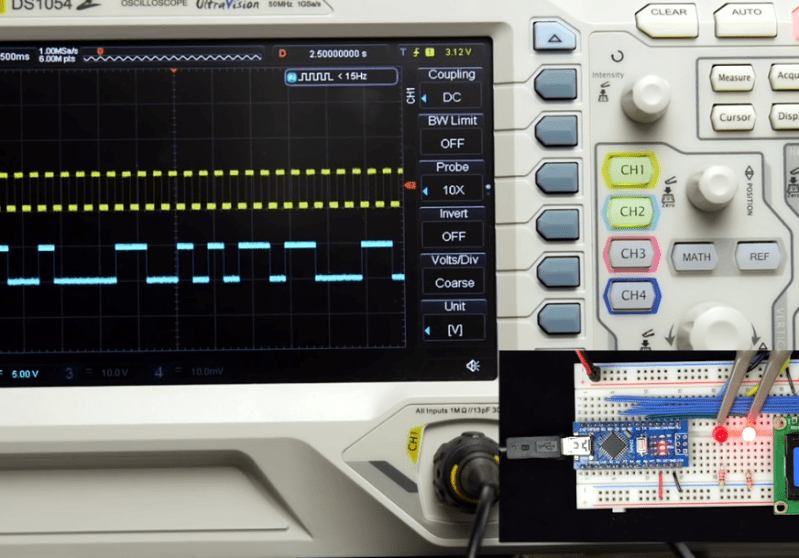

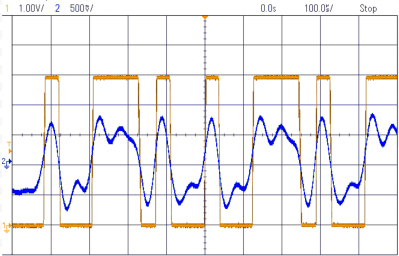

There is a piece of Javascript code in a browser into which you enter your WiFi credentials, which are then expressed through the speaker as a set of FSK tones to be picked up by a microphone on the Thing. They can then be decoded into the credentials, and the Thing can connect. All the code is available, on GitHub, should you fancy it yourself.

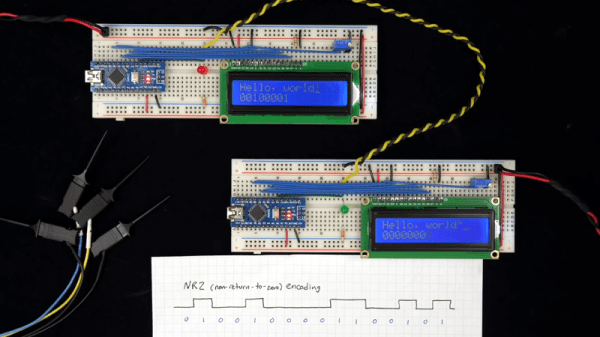

Of course, this is nothing new, as any owner of an 8-bit machine that had a cassette interface will tell you. And on the face of it it’s much easier than those awkward impromptu hotspots with a web interface to which you connect and pass on your credentials. But while we quite like the convenience, we can’t help wondering whether expressing the credentials in audible free space might be a bit too insecure for many readers. The technique however remains valid, and we’re sure that other less sensitive applications might be found for it. Meanwhile we hope he hasn’t inadvertently shared his WiFi password in the video below the break.