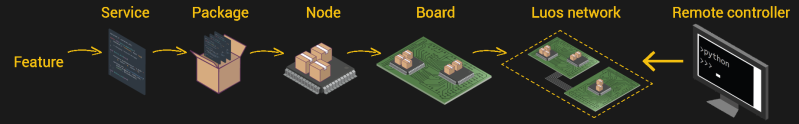

Those of us tasked with developing firmware for embedded systems have a quite a few hurdles to jump through compared to those writing for the desktop or mobile platforms. Solved problems such as code reuse or portability are simply harder. It was with considerable interest that we learnt of another approach to hardware abstraction, called Luos, which describes itself as micro-services for embedded systems.

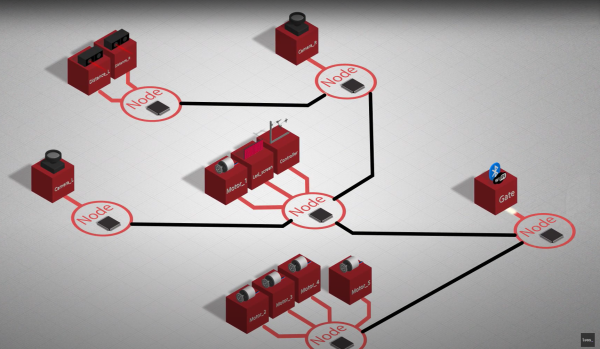

This open source project enables deployment of distributed architectures composed of collaborating micro-services. By containerizing applications and hardware drivers, interfaces to the various components are hidden behind a consistent API. It doesn’t even matter where a resource is located, multiple services may be running on the same microcontroller, or separate ones, yet they can communicate in the same way.

By following hardware and software design rules, it’s possible to create an architecture of cooperating computing units, that’s completely agnostic of the actual hardware. Microcontrollers talk at the hardware level with a pair of bidirectional signals, so the hardware cost is very low. It even integrates with ROS, so making robots is even easier.

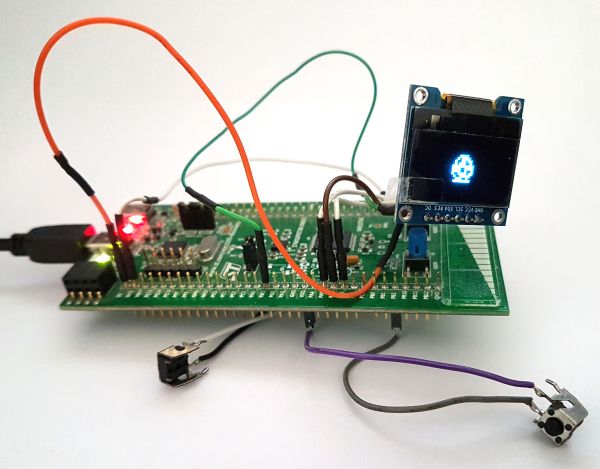

By integrating a special block referred to as a Gate, it is possible to connect to the architecture in real-time from a host computer via USB, WiFi, or serial port, and stream data out, feed data in, or deploy new software. The host software stack is based around Python, running under Jupyter Notebook, which we absolutely love.

Current compatibility is with many STM32 and ATSAM21 micros, so chances are good you can use it with whatever you have lying around, but more platforms are promised for the future.

Now yes, we’re aware of CMSIS, and the idea of Hardware Abstraction Layers (HALs) used as part of the platform-specific software kits, this is nothing new. But, different platforms work quite differently, and porting code from one to another, just because you can no longer get your preferred microcontroller any more, is a real drag we could all do without, so why not go clone the GitHub and have a look for yourselves?

Continue reading “With Luos Rapid Embedded Deployment Is Simplified”

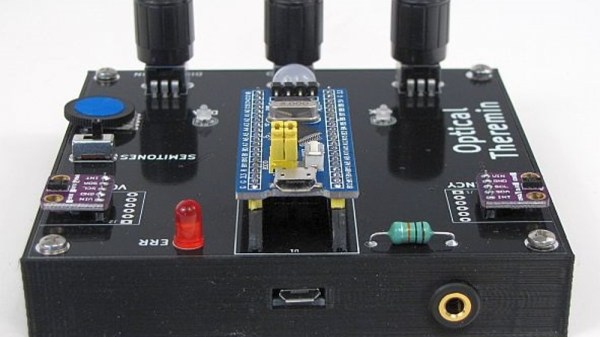

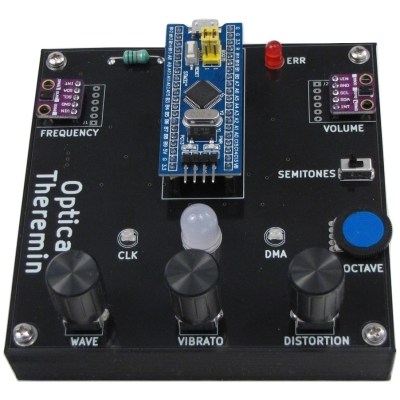

The design is based on a ‘

The design is based on a ‘