Occasionally, we find fun new electronic instruments in the wild and can’t resist sharing them with our readers. The item in question is the FNIRSI HRM-10 Internal resistance meter, which we show here being reviewed by [JohnAudioTech].

So what does it do, and why would you want one? The device is designed to measure batteries so you can quickly determine their health. Its operating principle also allows it to do a decent job of measuring low-resistance parts, which is not necessarily as easy to achieve with the garden variety multimeter, especially the low-end ones. We reckon it would be useful in the field for checking the resistance of switches and relays, possibly in automotive or industrial applications. The four-pin connector is needed because there are two wires per probe, making a Kelvin (also known as four-wire) connection.

Likely, the operating principle is to apply a varying load to the battery under test and then measure the voltage drop. The slope of the voltage sag vs load is a reasonable estimate of the resistance of the source, at least for the applied voltage range. The Kelvin connection uses one pair of wires to apply the test current from a relatively low-impedance source and the second pair to measure the voltage with a high input impedance. That way, the resistance of the probe wires can be calibrated out, giving a much more accurate measurement. Many lab-grade measurement equipment works this way.

Circling back to the HRM-10, [John] notes that it also supports limit testing, making it a helpful gauging tool for the workbench when sorting through many batteries. Data logging and the ability to upload to a computer completes the feature set, which is quite typical for this level of product now. Gone are the days of keeping a manual logbook next to the instrument stack and writing everything down by hand!

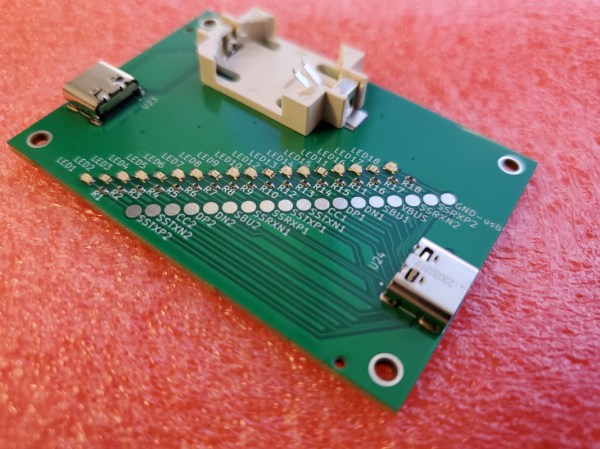

We’ve touched on measuring battery internal resistance before, but it was a while ago. Regarding Kelvin connections, here’s a quick guide and a hack upgrading a cheap LCR to support 4-wire probes.

Continue reading “The FNIRSI HRM-10 Internal Resistance Meter” →