Morse code might seem obsolete but for situations with extremely limited bandwidth it’s often still the best communications option available. The code requires a fair amount of training to use effectively, though, and even proficient radio operators tend to send only around 20 words per minute. As a result of the reduced throughput, a type of language evolved around Morse code which, like any language, has evolved and changed over time. QRP initially meant something akin to “you are overloading my receiver, please reduce transmitter power” but now means “operating radios at extremely low power levels”. [MIKROWAVE1] explores some of the earlier options for QRP radios in this video.

There’s been some debate in the amateur radio community over the years over what power level constitutes a QRP operation, but it’s almost certainly somewhere below 100 watts, and while the radios in this video have varying power levels, they tend to be far below this upper threshold, with some operating on 1 watt or less. There are a few commercial offerings demonstrated here, produced from the 70s to the mid-80s, but a few are made from kits as well. Kits tended to be both accessible and easily repairable, with Heathkit being the more recognizable option among this category. To operate Morse code (or “continuous wave” as hams would call it) only requires a single transistor which is why kits were so popular, but there are a few other examples in this video with quite a few more transistors than that. In fact, there are all kinds of radios featured here with plenty of features we might even consider modern by today’s standards; at least when Morse code is concerned.

QRP radios in general are attractive because they tend to be smaller, simpler, and more affordable. Making QRP contacts over great distances also increases one’s ham radio street cred, especially when using Morse, although this benefit is more intangible. There’s a large trend going on in the radio world right now surrounding operating from parks and mountain peaks, which means QRP is often the only way to get that done especially when operating on battery power. Modern QRP radios often support digital and voice modes as well and can have surprisingly high prices, but taking some cues from this video about radios built in decades past could get you on the radio for a minimum or parts and cost, provided you can put in the time.

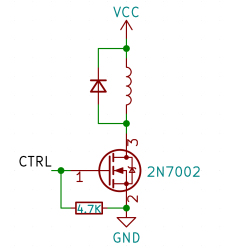

Perhaps, that’s the single most popular use for an NPN transistor – driving coils, like relays or solenoids. We are quite used to driving relays with BJTs, typically an NPN – but it doesn’t have to be a BJT, FETs often will do the job just as fine! Here’s an N-FET, used in the exact same configuration as a typical BJT is, except instead of a base current limiting resistor, we have a gate-source resistor – you can’t quite solder the BJT out and solder the FET in after you have designed the board, but it’s a pretty seamless replacement otherwise. The freewheel (back EMF protection) diode is still needed for when you switch the relay and the coil produces wacky voltages in protest, but hey, can’t have every single aspect be superior.

Perhaps, that’s the single most popular use for an NPN transistor – driving coils, like relays or solenoids. We are quite used to driving relays with BJTs, typically an NPN – but it doesn’t have to be a BJT, FETs often will do the job just as fine! Here’s an N-FET, used in the exact same configuration as a typical BJT is, except instead of a base current limiting resistor, we have a gate-source resistor – you can’t quite solder the BJT out and solder the FET in after you have designed the board, but it’s a pretty seamless replacement otherwise. The freewheel (back EMF protection) diode is still needed for when you switch the relay and the coil produces wacky voltages in protest, but hey, can’t have every single aspect be superior.

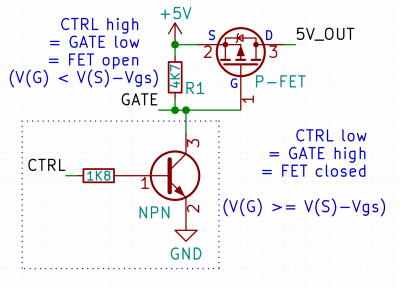

Here’s a simple FET circuit that lets you switch power to, say, a USB port, kind of like a valve that interrupts the current flow. This circuit uses a P-FET – to turn the power on, open the FET by bringing the GATE signal down to ground level, and to switch it off, close the FET by bringing the GATE back up, where the resistor holds it by default. If you want to control it from a 3.3 V MCU that can’t handle the high-side voltage on its pins, you can add a NPN transistor section as shown – this inverts the logic, making it into a more intuitive “high=on, low=off”, and, you no longer risk a GPIO!

Here’s a simple FET circuit that lets you switch power to, say, a USB port, kind of like a valve that interrupts the current flow. This circuit uses a P-FET – to turn the power on, open the FET by bringing the GATE signal down to ground level, and to switch it off, close the FET by bringing the GATE back up, where the resistor holds it by default. If you want to control it from a 3.3 V MCU that can’t handle the high-side voltage on its pins, you can add a NPN transistor section as shown – this inverts the logic, making it into a more intuitive “high=on, low=off”, and, you no longer risk a GPIO!