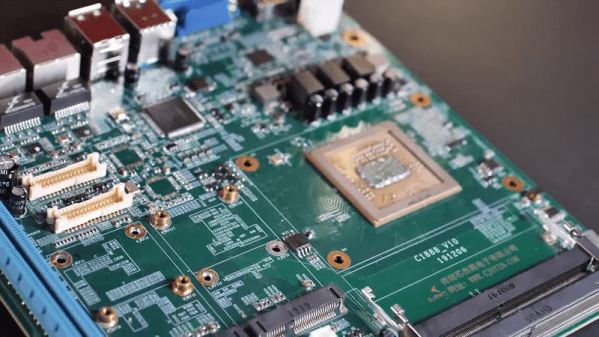

Although DIY PCB making has made great strides since the early days of chemical etching, there’s one fly in the ointment: vias. These connect individual layers of the board with a conductive tube, and are essential for dual-layer PCBs, never mind boards with a larger layer stack. The industry standard way of producing them is rather cumbersome and doesn’t scale well to a hobby or prototyping context. Might there be a better way? This is the question that [Levi Janssen] set out to answer with a new home PCB manufacturing project.

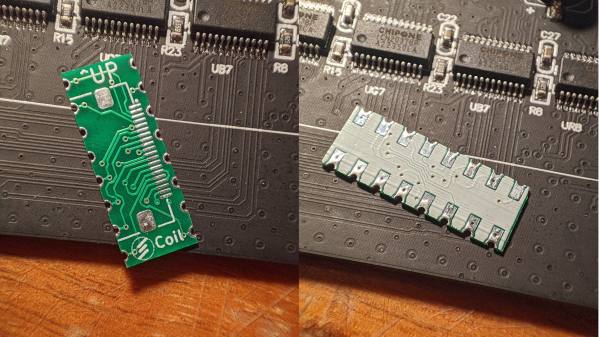

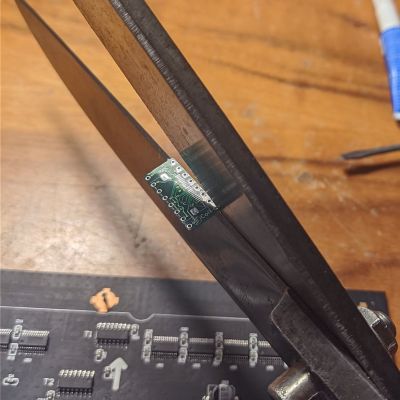

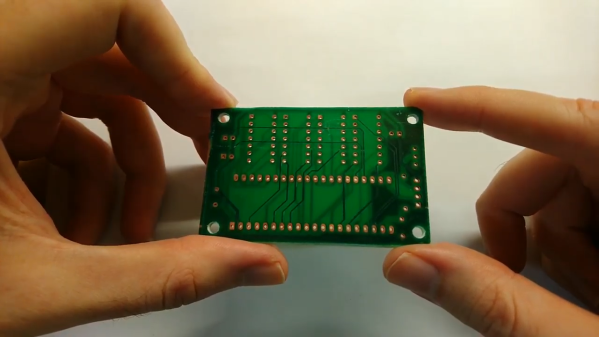

The goal here is to still electroplate the vias as with the commercial solution, just without having to use chemical baths. This way it should be suitable for an automated setup, with a tool head that performs the coating of the via with a high-resistance conductive ink before the electroplating step, all without submerging the entire PCB. After an initial experiment showed promising results, [Levi] committed to a full prototype.

This turned out to be a bridge too far, so the prototype was scaled down to a simpler machine. This is where the main issue with electroplating one via at a time became clear, as a standard 0.3 mm via takes easily 10 minutes to electroplate, even with an increase in voltage. At that point ordering a PCB from China becomes the faster option if you have enough vias in the design. Fortunately [Levi] figures he may have some solutions there, so we’ll have to wait and see what those are in the next installment. The video is below the break.

Continue reading “Electroplating DIY PCB Vias At Home Without Chemical Baths”