Snooping in on satellites is getting to be quite popular, enough so that the number of people advancing the state of the art — not to mention the wealth of satellites transmitting signals in the clear — has almost made the hobby too easy. An SDR, a homebrew antenna, and some off-the-shelf software, and you too can see weather satellite images on your screen in real time.

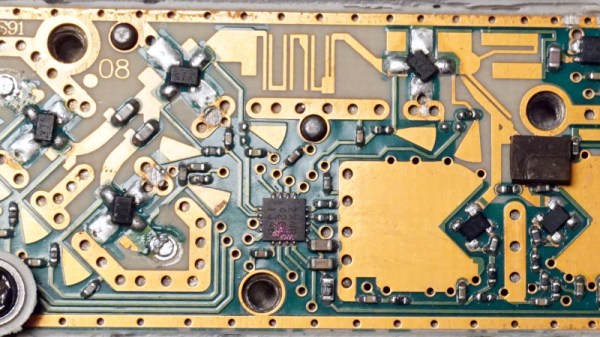

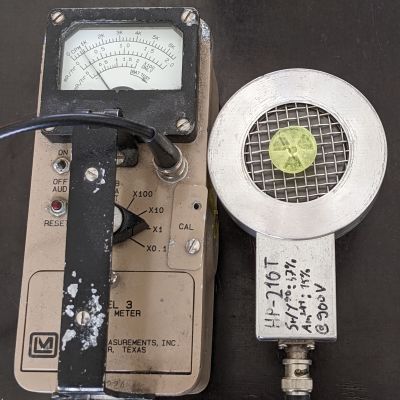

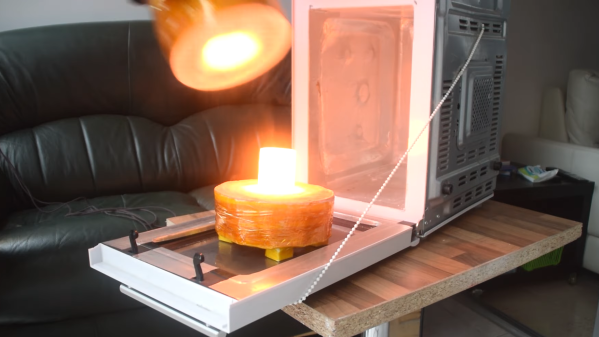

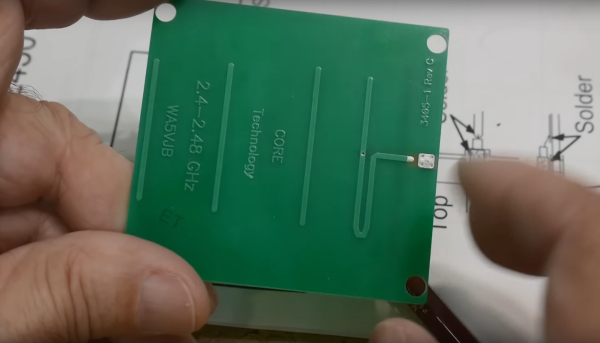

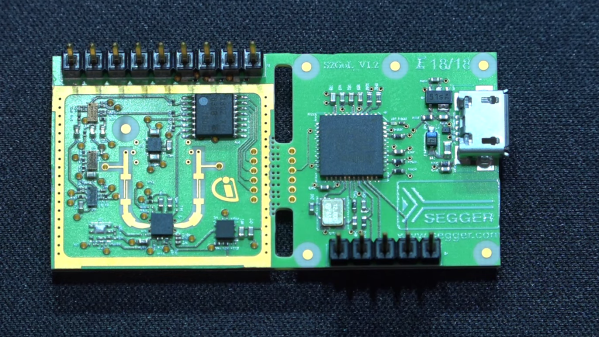

But where’s the challenge? That seems to be the question [dereksgc] asked and answered by tapping into S-band telemetry from an obsolete satellite. Most satellite hunters focus on downlinks in the L-band or even the VHF portion of the spectrum, which are within easy reach of most RTL-SDR dongles. However, the Coriolis satellite, which was launched in 2003, has a downlink firmly in the S-band, which at 2.2-GHz puts it just outside the high end of an RTL-SDR. To work around this, [dereksgc] bought a knock-off HackRF SDR and couple it with a wideband low-noise amplifier (LNA) of his own design. The dish antenna is also homebrewed from a used 1.8-m dish and a custom helical antenna for the right-hand circular polarized downlink signal.

As the video below shows, receiving downlink signals from Coriolis with the rig wasn’t all that difficult. Even with manually steering the dish, [dereksgc] was able to record a couple of decent passes with SDR#. Making sense of the data from WINDSAT, a passive microwave polarimetric radiometer that’s the main instrument that’s still working on the satellite, was another matter. Decoded with SatDump and massaged with Gimp, the microwave images of Europe are at least recognizable, mostly due to Italy’s distinctive shape.

Despite the distortion, seeing the planet’s surface via the microwaves emitted by water vapor is still pretty cool. If more traditional weather satellite images are what you’re looking for, those are pretty cool too.

Continue reading “Using An Old Satellite To See The Earth In A New Light”