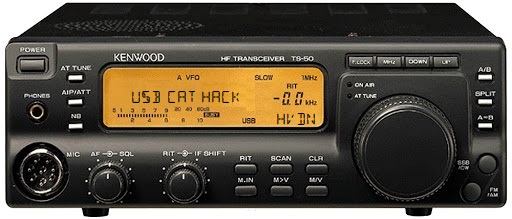

The modern ham radio shack can take many forms. Some are shrines the “boat anchor” radios of old, named for their considerable weight. Others are simply a small, unassuming software-defined radio (SDR) hooked up to a laptop. Nowadays, many shacks fall somewhere in the middle. It’s not uncommon to find a sleek Icom IC-7300 sitting atop an ancient Hallicrafters SX-115 (which sounds suspiciously like the author’s setup). When a ham wants to work a digital mode such as FT-8, they will undoubtedly reach for a newer radio complete with USB (Universal Serial Bus in this case, not Upper Sideband) rig control — but what if the newest piece of equipment they have is a thirty-year-old Kenwood?

If that sounds like you, then fear not because [Steve Bossert] has you covered. He took his trusty Kenwood TS-50, a classic radio from 1993 whose most advanced feature is fuzzy logic, and upgraded it with USB (again, the serial bus) control.

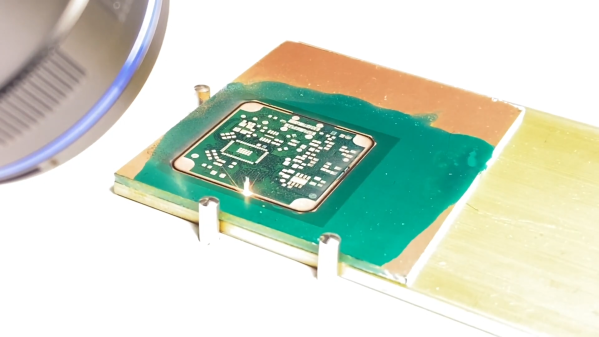

When Kenwood designed the TS-50, they had computer control in mind. There’s a hidden port on the bottom of the unit which reveals a connector that mates with Kenwood’s proprietary (and expensive) set of serial control cables. Thankfully, the engineers over at Kenwood decided to use UART for PC communication, so slapping a USB port in the radio’s case isn’t as daunting as it may sound. [Steve] picked up a CP2104 USB-TTL UART Serial Adapter and wired it up to the radio’s control port. After a bit of drilling, screwing, and gluing, the radio had an upgraded (and non-proprietary!) interface compatible with the ever-popular hamlib. While this doesn’t cover all radio control functions, it gets you tuning, which is pretty important. For a fully modern radio experience, [Steve] suggests using the 8-pin mic connector along with an interface such as Rigblaster or Signalink. This adds PTT and audio signal routing.

If you want to try this for yourself, be sure to check out [Steve]’s extremely well-documented writeup. You could even take this a step further and control your TS-50 from your smartphone with this HTML5 interface we saw a few months back.