Power distribution units, as the name implies, are indispensable tools to have available in a server rack. They can handle a huge amount of power for demands of intensive computing and do it in a way that the wiring is managed fairly well. Plenty of off-the-shelf solutions have remote control or automation capabilities as well, but finding none that fit [fmarzocca]’s needs or price range, he ended up building his own essentially from scratch that powers his home automation system.

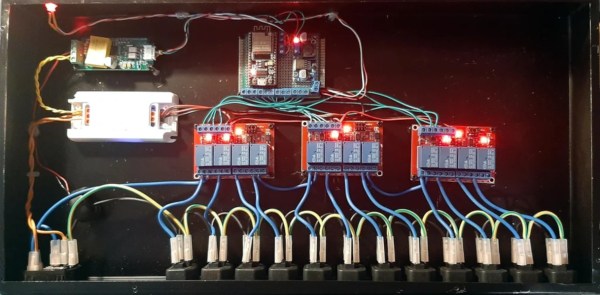

Because it is the power supply for a home automation system, each of the twelve outlets in this unit needed to be individually controllable. For that, three four-channel relay boards were used, each driven by an output on an ESP32. The ESP32 is running the Tasmota firmware to keep from having to reinvent the wheel, while MQTT was chosen as a protocol for controlling these outlets to allow for easy integration with the existing Node-RED-based home automation system. Not only is control built in to each channel, but the system can monitor the power consumption of each outlet individually as well. The entire system is housed in a custom-built sheet metal enclosure and painted to blend in well with any server rack.

Adding a system like this to a home automation system can simplify a lot of the design, and the scalable nature means that a system like this could easily be made much smaller or much larger without much additional effort. If you’d prefer to keep your hands away from mains voltage, though, we’ve seen similar builds based on USB power instead, with this one able to push around 2 kW.