[PeriscopeFilms] on YouTube has many old TV adverts and US government reels archived on their channel, with some really interesting subjects to dive in to. This first one we’re highlighting here is a 1958 film about NASA Soldering Techniques (Video, embedded below), which has some fascinating details about how things were done during the Space Race, and presumably, continue to be done. The overall message about cleanliness couldn’t really be any clearer if they tried — it’s so critical it looks like those chaps in the film spend far more time brushing and cleaning than actually wielding those super clean soldering irons.

Of particular note are some of the details of wire stripping and jointing with components, such as the use of a hot-wire device to remove the insulation from wire, rather than use the kind of stripper we have lying around that cuts into the insulation and slightly distorts the wire in the process. That just won’t do. If they did have to use a cutting-type stripper, it must be precisely the right size for job, and calibrated daily.

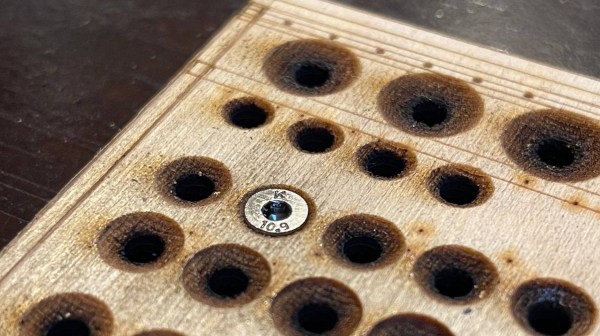

When soldering a pre-tinned wire to a leaded component, a clamp is required to prevent movement of the wire, as is a thermal shunt on the component lead to protect the delicate component from excess heat. They even specify how much to wrap a wire around a terminal to be soldered, never bending the wire more than 180 degrees.

The bottom line in all this is, is that the work must be as perfect as is possible, as there is very little chance of sending someone up to fix a dodgy soldering job, once the assembly is hurtling around the planet. They call it too much of a science to be called an art and too much art to be called a science, and we can sure appreciate that.

As you would expect (and it’s not exactly a big secret) NASA has some very exacting standards for assembly of all hardware, like this great workmanship standard, which is well worth studying. Soldering is an important subject for many of us, we’ve covered the subject of solder metallurgy, as well as looking at how ancient hardware hackers soldered without the benefit of much modern knowledge.

Continue reading “NASA Hardware Techniques: Soldering Space Electronics Like It’s 1958”

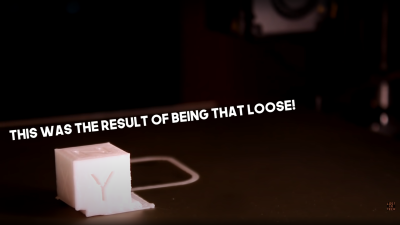

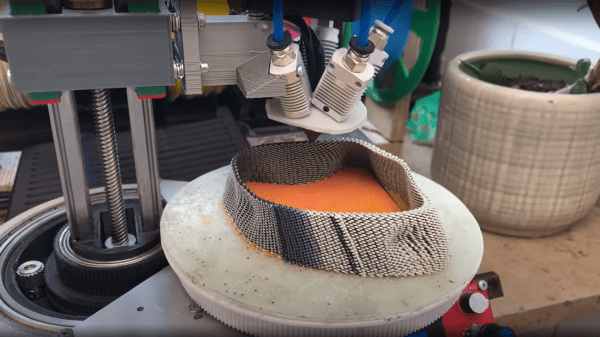

trick is to use the same weight maps and simply map colours to blender text blocks which are injected into the gcode at export time. These gcode blocks can be used swap tool heads or extruders, enabling blending of multiple filament colours or types in the same object.

trick is to use the same weight maps and simply map colours to blender text blocks which are injected into the gcode at export time. These gcode blocks can be used swap tool heads or extruders, enabling blending of multiple filament colours or types in the same object.