If you wave your hand under the water’s surface, you get a pattern of ripples on the surface shortly thereafter. Now imagine working that backwards: you want to produce particular ripples on the surface, so how do you wiggle around the water molecules underneath?

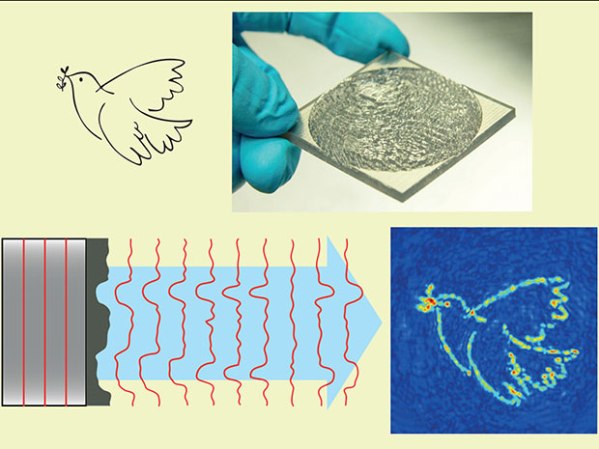

That’s the project that a crew from the University of Navarre in Spain Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems undertook. Working backwards from the desired surface waves to the excitation underwater is “just” a matter of math and physics. The question is then how to produce the right, incredibly irregular, wavefront. The researchers’ answer was 3D printing.

The idea is that, by creating the desired ripples on the water’s surface, the researchers will be able to move things around. We’ve actually seen this done before in air by [mikeselectricstuff], and a more sophisticated version from the University of Navarre in Spain uses multiple ultrasonic transducers and enables researchers to move tiny objects around in mid-air.

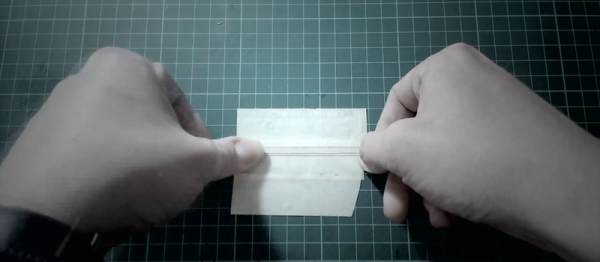

What’s cool about the work done underwater by the Navarre Max Planck Institute group is that all they’re doing is printing out a 3D surface and wiggling it up and down to make the waves. The resulting surface wave patterns are limited in comparison to the active systems, but the apparatus is so much simpler that it ought to be useful for hackers with 3D printers. Let the era of novelty pond hacking begin!