Playing around with FPGAs used to be a daunting prospect. You had to fork out a hundred bucks or so for a development kit, sign the Devil’s bargain to get your hands on a toolchain, and only then can you start learning. In the last few years, a number of forces have converged to bring the FPGA experience within the reach of even the cheapest and most principled open-source hacker.

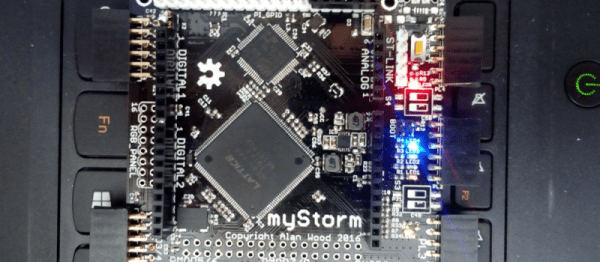

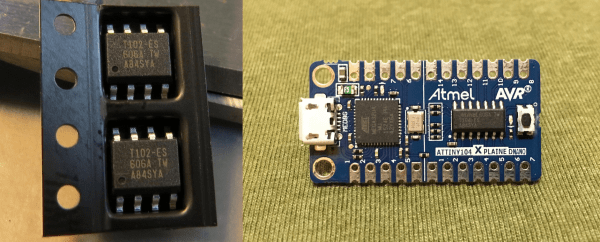

[Ken Boak] and [Alan Wood] put together a no-nonsense FPGA board with the goal of getting the price under $30. They basically took a Lattice iCE40HX4K, an STMF103 ARM Cortex-M3 microcontroller, some SRAM, and put it all together on a single board.

The Lattice part is a natural choice because the IceStorm project created a full open-source toolchain for it. (Watch [Clifford Wolf]’s presentation). The ARM chip is there to load the bitstream into the FPGA on boot up, and also brings USB connectivity, ADC pins, and other peripherals into the mix. There’s enough RAM on board to get a lot done, and between the ARM and FPGA, there’s more GPIO pins than we can count.

Modeling an open processor core? Sure. High-speed digital signal capture? Why not. It even connects to a Raspberry Pi, so you could use the whole affair as a high-speed peripheral. With so much flexibility, there’s very little that you couldn’t do with this thing. The trick is going to be taming the beast. And that’s where you come in.