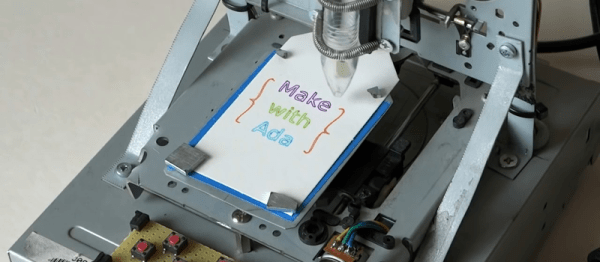

[Fabian Chouteau] built a plotter out of CD-ROM parts. Yawn, you say? Besides being a beautiful physical build, this one has a twist. He wrote the software and firmware for the entire project himself, in Ada.

Ada is currently number two on our list of oddball programming languages that should be useful for embedded programming. It’s vaguely Pascal-y, but with some modern object-oriented twists. It was developed for safety-critical, real-time embedded systems (by the US Department of Defense), and is used in things like airplanes, rockets, and the French TGV trains. If that sounds like overkill for your projects, [Fabian]’s project shows that it’s still very tractable.

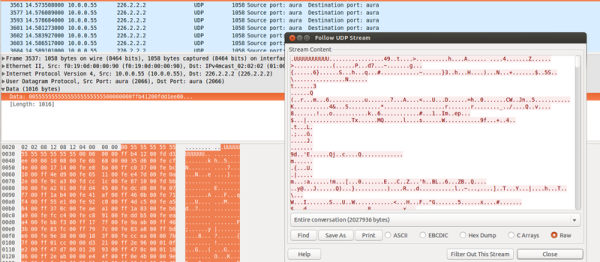

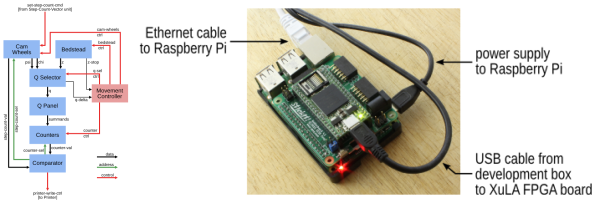

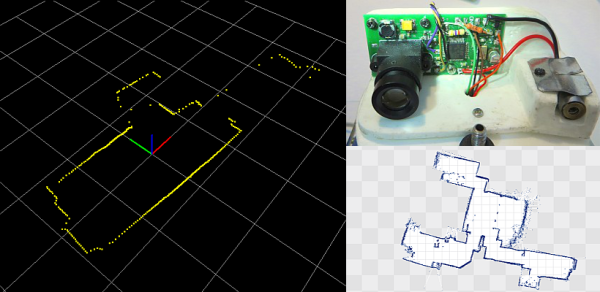

In his GitHub, he re-implements the GRBL G-code generator and then writes a GUI front-end for it. In his writeup, he mentions that the firmware and its simulator for the front-end use exactly the same code which is quite a nice trick, and guarantees no (firmware) surprises when moving from the modelled device to the real thing.

We looked quickly around for Ada resources and came up with: GNAT, the GNU Ada compiler, and its derivatives: GNAT for ARM (STM32-flavor), ARM-Ada (LPC21xx flavor), AVR-Ada, and MSP430-Ada.

Any of you out there use Ada in embedded work? We’d love to hear your thoughts.

Continue reading “Pen-Plotter Firmware Written Completely In Ada”