The Sci-Fi Contest closed out on Monday, and we put our heads together and picked our favorites. And it was no easy task, because in addition to many of the projects simply looking stellar, many went all-out on the documentation as well, making these stellar examples that we can all learn from, whether you’re into sci-fi or not. But who are we kidding? From the responses we got, you are.

The Winners

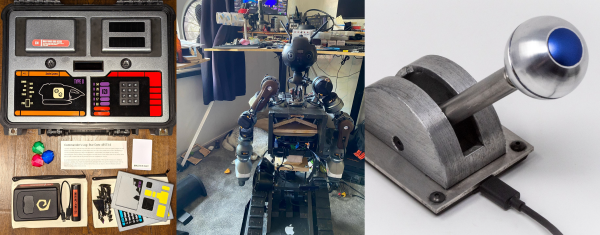

[RubenFixit]’s Star Trek Shuttle Console is a Trek themed escape room in a box. The project’s extraordinary attention to detail and exhaustive project logs absolutely won our judges heart. From the LCARS graphics to the 3D printed isolinear chip bays and mimetic crystals, it’s all there. [Ruben] estimates about 300 hours of work went into this one, and it shows.

We had no shortage of robotic projects in the contest, but [RudyAramayo]’s R.O.B. won our judges over. This one is not a joke, weighing in at over 140 lbs of custom metalwork and righteous treads. It’s also made out of some expensive hardware all around, so maybe this isn’t your weekend-build robot. We love the comment on the Arduino test code suite: “For gods sake man, you must test your code when it becomes an autonomous vehicle.”

Finally, [zapwizard]’s Functional Razor Crest Control Lever is a prop and a video game controller in one. We can totally see Grogu playing with this, and we were wowed by the attention to detail in the physical build — with custom gears and a speed limiter — as well as the attention to prop-making detail. Some parts are custom-cut stainless steel plates. 3D printed parts are covered in aluminum tape and chemically aged. Awesome. Oh yeah, it’s also a working USB joystick.

These three winners will be receiving a $150 shopping spree at Digi-Key.

![5315181650477410414_thumbnail [Nick Poole]'s thermionic converter array](https://i0.wp.com/hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/5315181650477410414_thumbnail.png?w=396&h=396&crop=1&ssl=1)

![5079001583214379162_thumbnail [Anuradha Gunawardhana]'s 18650 Pack](https://i0.wp.com/hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/5079001583214379162_thumbnail.png?w=396&h=396&crop=1&ssl=1)

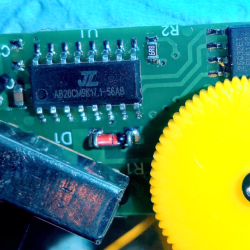

It all started when [Big Clive] ordered a chintzy Chinese musical meditation flower and found a black blob. But tantalizingly, the shiny plastic mess also included a 2 MB flash EEPROM. The questions then is: can one replace the contents with your own music? Spoiler: yes, you can! [Sprite_tm] and a team of Buddha Chip Hackers distributed across the globe got to work. (

It all started when [Big Clive] ordered a chintzy Chinese musical meditation flower and found a black blob. But tantalizingly, the shiny plastic mess also included a 2 MB flash EEPROM. The questions then is: can one replace the contents with your own music? Spoiler: yes, you can! [Sprite_tm] and a team of Buddha Chip Hackers distributed across the globe got to work. ( Bad pattern number one is XOR. Used correctly, XORing can be a force for good, but if you XOR your key with zeros, naturally, you get the key back as your ciphertext. And this data had a lot of zeros in it. That means that there were many long strings that started out the same, but they seemed to go on forever, as if they were pseudo-random. Bad crypto pattern number two is using a linear-feedback shift register for your pseudo-random numbers, because the parameter space is small enough that [Sprite_tm] could just brute-force it. At the end, he points out their third mistake — making the encryption so fun to hack on that it kept him motivated!

Bad pattern number one is XOR. Used correctly, XORing can be a force for good, but if you XOR your key with zeros, naturally, you get the key back as your ciphertext. And this data had a lot of zeros in it. That means that there were many long strings that started out the same, but they seemed to go on forever, as if they were pseudo-random. Bad crypto pattern number two is using a linear-feedback shift register for your pseudo-random numbers, because the parameter space is small enough that [Sprite_tm] could just brute-force it. At the end, he points out their third mistake — making the encryption so fun to hack on that it kept him motivated!