Maybe you heard about the anger surrounding Twitter’s automatic cropping of images. When users submit pictures that are too tall or too wide for the layout, Twitter automatically crops them to roughly a square. Instead of just picking, say, the largest square that’s closest to the center of the image, they use some “algorithm”, likely a neural network, trained to find people’s faces and make sure they’re cropped in.

The problem is that when a too-tall or too-wide image includes two or more people, and they’ve got different colored skin, the crop picks the lighter face. That’s really offensive, and something’s clearly wrong, but what?

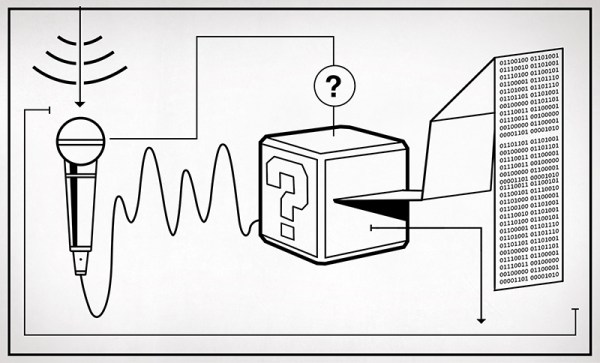

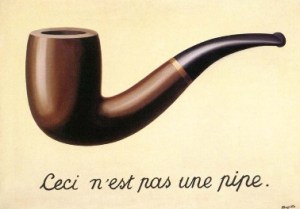

A neural network is really just a mathematical equation, with the input variables being in these cases convolutions over the pixels in the image, and training them essentially consists in picking the values for all the coefficients. You do this by applying inputs, seeing how wrong the outputs are, and updating the coefficients to make the answer a little more right. Do this a bazillion times, with a big enough model and dataset, and you can make a machine recognize different breeds of cat.

What went wrong at Twitter? Right now it’s speculation, but my money says it lies with either the training dataset or the coefficient-update step. The problem of including people of all races in the training dataset is so blatantly obvious that we hope that’s not the problem; although getting a representative dataset is hard, it’s known to be hard, and they should be on top of that.

Which means that the issue might be coefficient fitting, and this is where math and culture collide. Imagine that your algorithm just misclassified a cat as an “airplane” or as a “lion”. You need to modify the coefficients so that they move the answer away from this result a bit, and more toward “cat”. Do you move them equally from “airplane” and “lion” or is “airplane” somehow more wrong? To capture this notion of different wrongnesses, you use a loss function that can numerically encapsulate just exactly what it is you want the network to learn, and then you take bigger or smaller steps in the right direction depending on how bad the result was.

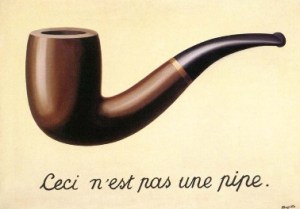

Let that sink in for a second. You need a mathematical equation that summarizes what you want the network to learn. (But not how you want it to learn it. That’s the revolutionary quality of applied neural networks.)

Now imagine, as happened to Google, your algorithm fits “gorilla” to the image of a black person. That’s wrong, but it’s categorically differently wrong from simply fitting “airplane” to the same person. How do you write the loss function that incorporates some penalty for racially offensive results? Ideally, you would want them to never happen, so you could imagine trying to identify all possible insults and assigning those outcomes an infinitely large loss. Which is essentially what Google did — their “workaround” was to stop classifying “gorilla” entirely because the loss incurred by misclassifying a person as a gorilla was so large.

This is a fundamental problem with neural networks — they’re only as good as the data and the loss function. These days, the data has become less of a problem, but getting the loss right is a multi-level game, as these neural network trainwrecks demonstrate. And it’s not as easy as writing an equation that isn’t “racist”, whatever that would mean. The loss function is being asked to encapsulate human sensitivities, navigate around them and quantify them, and eventually weigh the slight risk of making a particularly offensive misclassification against not recognizing certain animals at all.

I’m not sure this problem is solvable, even with tremendously large datasets. (There are mathematical proofs that with infinitely large datasets the model will classify everything correctly, so you needn’t worry. But how close are we to infinity? Are asymptotic proofs relevant?)

Anyway, this problem is bigger than algorithms, or even their writers, being “racist”. It may be a fundamental problem of machine learning, and we’re definitely going to see further permutations of the Twitter fiasco in the future as machine classification is being increasingly asked to respect human dignity.

Back in the before-times, we would meet up, talk about our ongoing hacks, and invariably someone would say “oh you need an X, I’ve got half a box of them” and send you one. Or maybe you’d be the one with the extra widgets on hand. I know I’ve happily been in both positions.

Back in the before-times, we would meet up, talk about our ongoing hacks, and invariably someone would say “oh you need an X, I’ve got half a box of them” and send you one. Or maybe you’d be the one with the extra widgets on hand. I know I’ve happily been in both positions.