A while back, I bought a cheap spectrum analyser via AliExpress. I come from the age when a spectrum analyser was an extremely expensive item with a built-in CRT display, so there’s still a minor thrill to buying one for a few tens of dollars even if it’s obvious to all and sundry that the march of technology has brought within reach the previously unattainable. My AliExpress spectrum analyser is a clone of a design that first appeared in a German amateur radio magazine, and in my review at the time I found it to be worth the small outlay but a bit deaf and wide compared to its more expensive brethren. Continue reading “Perhaps It’s Time To Talk About All Those Fakes And Clones”

Author: Jenny List3312 Articles

A Cycle-Accurate Intel 8088 Core For All Your Retro PC Needs

A problem faced increasingly by retrocomputer enthusiasts everywhere is the supply of chips. Once a piece of silicon goes out of production its demand can be supplied for a time by old stock and second hand parts, but as they become rare so the cost of what can be dubious parts accelerates out of reach. Happily for CPUs at least, there’s a ray of hope in the form of FPGA-based cores which can replace the real thing, and for early PC owners there’s a new one from [Ted Fried]. MCL86 is a cycle accurate Intel 8088 FPGA Core that can be used within an FPGA design or as a standalone in-circuit replacement for a real 8088. It even has a full-speed mode that sacrifices cycle accuracy and can accelerate those 8088 instructions by 400%.

Reading the posts on his blog, it’s clear that this is a capable design, and it’s even been extended with a mode that adds cache RAM to mirror the system memory at the processor’s speed. You can find all the code in a GitHub repository should you be curious enough to investigate for yourself. We’ve pondered in the past where the x86 single board computers are, perhaps it could be projects like this that provide some of them.

A Dead Photographic Format Rises From The Ashes

Sometimes we stumble upon a hack that’s not entirely new but which is still pretty exceptional. So it is with [Hèrm Hofmeyer]’s guide to recreating a film cartridge for the Kodak Disc photographic format. It’s written in 2020, but describing a project around a decade old.

The disc format was Kodak’s great hope in the 1980s, the ultimate in photographic convenience in which the film was a 16-shot circular disc in a thin cartridge. Though the cameras were at the consumer end of the market they were more sophisticated than met the eye, with the latest electronics for the time and some innovative plastic multi-element aspherical lenses. It failed in the face of better compact 35 mm cameras because the convenience of the disc wasn’t enough to make up for the relatively small negative and that few labs had the specialized printing equipment to get the best results from the format. The cameras faded from view, and the film ceased manufacture at the end of the 1990s.

The biggest hurdle to creating a Disc cartridge comes in the cartridge shells themselves. It’s solved by sourcing them second-hand from Film Rescue International, a specialist in developing expired photographic film. The stages follow the cutting of a film disc, perforating its edges, and fitting it into the cartridge. It’s an exact enough process in the pictures, and it’s worth remembering that in the real cartridges it must be done in the dark.

This is an interesting piece of work for anyone with an interest in photography, and while the Disc cameras were always a consumer snapshot camera we can see that it would appeal to those influenced by Lomography. We wish we could get our hands on a Disc cartridge, an maybe CAD up a 3D printable version to make it more accessible.

Rescue That Dead Xbox With An External PSU

There is nothing worse than that sinking feeling as a computer or other device fails just after its warranty has expired. [Robotanv] had it with his Xbox Series S whose power supply failed, and was faced with either an online sourced PSU of uncertain provenance, or a hefty bill from Microsoft for a repair. He chose to do neither, opening up his console and replacing the broken PSU with a generic external model. See the video below the break.

The Xbox appears surprisingly well designed as a modular unit, so accessing and unplugging its PSU was quite easy. To his surprise he found that the connections were simply two wires, positive and negative lines for 12 V. The solution was to find a suitably beefy 12 V supply and wire it up, before continuing gaming.

Beyond that simple description lies a bit more. The original was a 160 W unit so he’s taken a gamble with a 120 W external brick. He’s monitoring its temperature carefully to make sure, but with his gaming it has not been a problem. Then there’s the board wiring, which he appears to have soldered to pads on the PCB. We might have tried to find something that fit the original spade connectors instead, but yet again it hasn’t caused him any problems. We’d be curious to see what has failed in the original PSU. Meanwhile we’re glad to see this Xbox ride again, it’s more than can be said for one belonging to a Hackaday colleague.

Continue reading “Rescue That Dead Xbox With An External PSU”

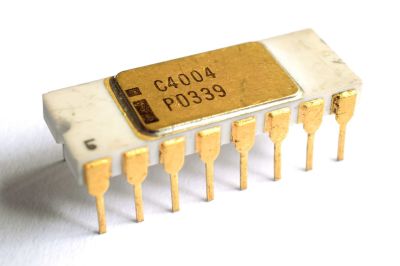

Ask Hackaday: When It Comes To Processors, How Far Back Can You Go?

When it was recently announced that the Linux kernel might drop support for the Intel 486 line of chips, we took a look at the state of the 486 world. You can’t buy them from Intel anymore, but you can buy clones, which are apparently still used in embedded devices. But that made us think: if you can’t buy a genuine 486, what other old CPUs are still in production, and which is the oldest?

Defining A Few Rules

There are a few obvious contenders that immediately come to mind, for example both the 6502 from 1975 and the Z80 from 1976 are still readily available. Some other old silicon survives in the form of cores incorporated into other chips, for example the venerable Intel 8051 microcontroller may have shuffled off this mortal coil as a 40-pin DIP years ago, but is happily housekeeping the activities of many far more modern devices today. Still further there’s the fascinating world of specialist obsolete parts manufacturing in which a production run of unobtainable silicon can be created specially for an extremely well-heeled customer. Should Uncle Sam ever need a crate of the Intel 8080 from 1974 for example, Rochester Electronics can oblige.

Continue reading “Ask Hackaday: When It Comes To Processors, How Far Back Can You Go?”

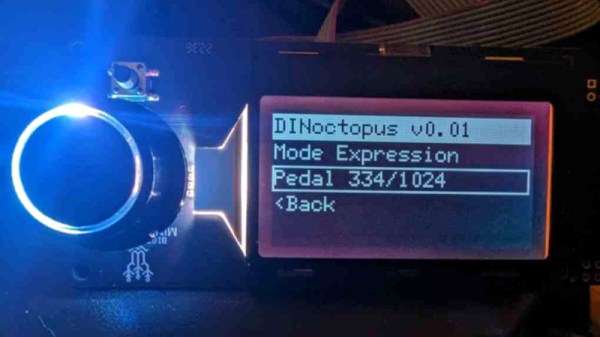

A Cheap 3D Printer Control Panel As A General Purpose Interface

Browsing the usual websites for Chinese electronics, there are a plethora of electronic modules for almost every conceivable task. Some are made for the hobbyist or experimenter market, but many of them are modules originally designed for a particular product which can provide useful functionality elsewhere. One such module, a generic control panel for 3D printers, has caught the attention of [Bjonnh]. It contains an OLED display, a rotary encoder, and a few other goodies, and he set out to make use of it as a generic human interface board.

To be reverse engineered were a pair of 5-pin connectors, onto which is connected the rotary encoder and display, a push-button, a set of addressable LEDs for backlighting, a buzzer, and an SD card slot. Each function has been carefully unpicked, with example Arduino code provided. Usefully the board comes with on-board 5 V level shifting.

While we all like to build everything from scratch, if there’s such an assembly commonly available it makes sense to use it, especially if it’s cheap. We’re guessing this one will make its way into quite a few projects, and that can only be a good thing.

A Practical Discrete 386

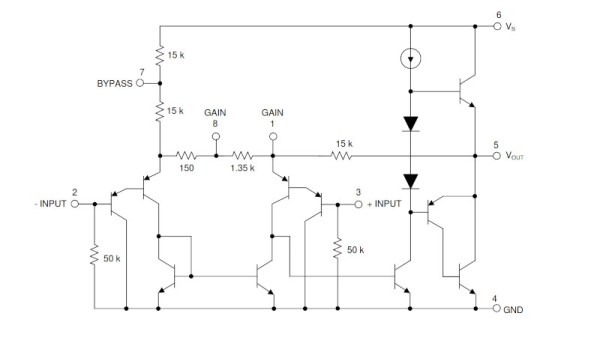

There are some chips that no matter how much the industry moves away from them still remain, exerting a hold decades after the ranges they once sat alongside have left the building. Such a chip is the 386, not the 80386 microprocessor you were expecting but the LM386, a small 8-pin DIP audio amplifier that’s as old as the Ark. the ‘386 can still be found in places where a small loudspeaker needs to be powered from a battery. SolderSmoke listener [Dave] undertook an interesting exercise with the LM386, reproducing it from discrete components. It’s a handy small discrete audio amplifier if you want one, but it’s also an interesting exercise in understanding analogue circuits even if you don’t work with them every day.

A basic circuit can be found in the LM386 data sheet (PDF), but as is always the case with such things it contains some simplifications. The discrete circuit has a few differences in the biasing arrangements particularly when it comes to replacing a pair of diodes with a transistor, and to make up for not being on the same chip it requires that the biasing transistors must be thermally coupled. Circuit configurations such as this one were once commonplace but have been replaced first by linear ICs such as the LM386 and more recently by IC-based switching amplifiers. It’s thus instructive to take a look at it and gain some understanding. If you’d like to know more, it’s a chip we’ve covered in detail.