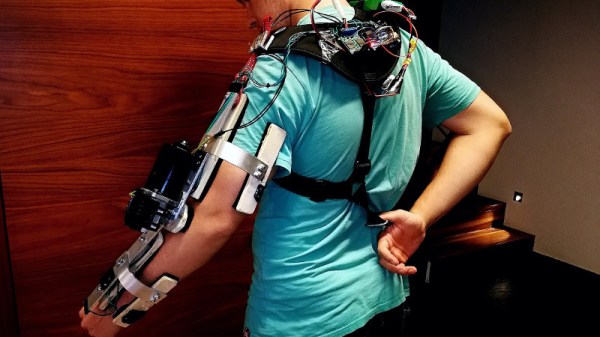

There are many ways to keep an eye on your 3D printer as it churns out the layers of your print. Most of us take a peek every now and then to ensure we’re not making plastic vermicelli, and some of us will go further with a Raspberry Pi camera or similar. [Uri Shaked] has taken this a step further, by adding a USB microscope on a custom bracket next to the hot end of his Creality Ender 3.

The bracket is not in itself anything other than a run-of-the-mill piece of 3D printing, but the interest comes in what can be done with it. The Ender 3 has a resolution of 12.5μm on X/Y axes, and 2.5μm on Z axes, meaning that the ‘scope can be positioned to within a hair’s-breadth of any minute object. Of course this achieves the primary aim of examining the integrity of 3D prints, but it also allows any object to be tracked or scanned with the microscope.

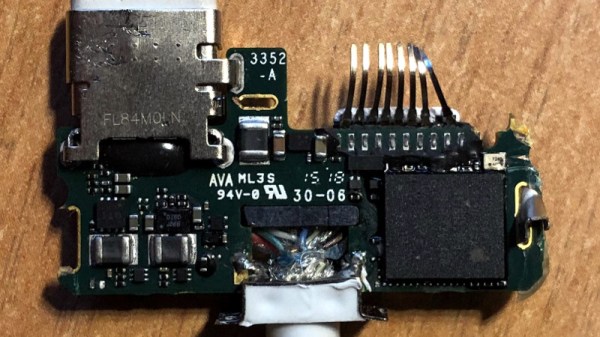

For example while examining a basil leaf, [Uri] noticed a tiny insect on its surface and was able to follow it with some hastily entered G-code. Better still, he took a video of the chase, which you can see below the break. From automated PCB quality control to artistic endeavours, we’re absolutely fascinated by the possibilities of a low-cost robotic microscope platform.

[Uri] is a perennial among Hackaday-featured projects, and has produced some excellent work over the years. Most recently we followed him through the production of an event badge.