Apple released a monitor stand not so long ago with an eye-watering price tag, and in the resulting fuss you might almost be forgiven for missing the news that they also released a new computer. The distinctive grille on the new Mac Pro caused some interest among Hackaday editors, with speculation rife as to how it had been machined. It seems we’re not alone in this, because [J. Peterson] sent us a link to his own detailed analysis.

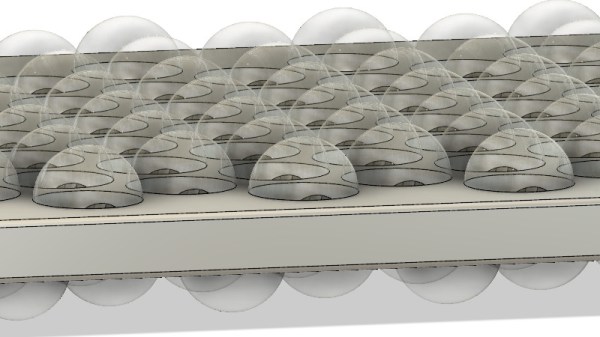

The key to the pattern lies in hemispherical holes milled part-way-through a piece of metal on a triangular tessellation, and intersecting with an identical set of holes milled at an offset from the other side. The analysis was done purely from online information as he doesn’t have a real Mac Pro, but using some clever trigonometry he is able to calculate the required offset as well as the hole depth. There are some STL files on Thingiverse, for the curious.

Should you wish to make your own copy of a Mac Pro grille you should therefore be able to use this information in programming a CNC mill to carve it from a piece of alloy plate. The interesting side of it from a manufacturing perspective though is that this is a complex shape that would be difficult to produce in numbers without either CNC or a very specialist one-off machine tool for this single purpose, and neither is a normal expenditure for a mere grille. Perhaps you might come close by rolling alloy plate between rollers whose profile matched the hole pattern, but in that event you would not equal the finish that they have achieved. Apple’s choice to use a relatively time-intensive CNC process in mass-production of a cosmetic part is probably in a large part a quality statement for their particular brand of consumer, but also sets a high bar to any would-be imitators. We applaud it for its engineering, even if we won’t be shelling out for that monitor stand.