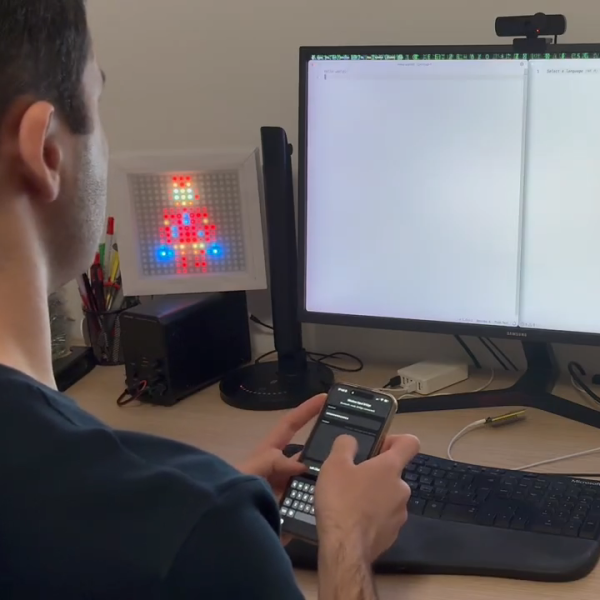

Sometimes you need to use a computer and you don’t have a spare keyboard and mouse on hand. [KoStard] figured an iPhone could serve as a passable replacement interface device. To that end, he built an adapter to let the phone act as a wireless keyboard and mouse on just about any modern machine.

To achieve this, [KoStard] grabbed an ESP32-S3 development board, and programmed it to act as a USB HID device to any machine attached over USB. It then listens out for Bluetooth LE communications from an iPhone equipped with the companion app. The app provides an on-screen keyboard on the iPhone that covers everything including special keys, symbols, and punctuation. You can also take advantage of the iPhone’s quality capacitive touchscreen, which emulates a nicely-responsive trackpad, with two-finger taps used for right clicking and two-finger drags for scroll. Latency is nice and low courtesy of the direct Bluetooth LE connection.

It’s a nifty build that is particularly useful in oddball situations where you might want a keyboard and mouse. For example, [KoStard] notes it’s a great way to control a Smart TV without having to do ugly slow “typing” on an infrared remote. We’ve seen his work before, too—previously building an adapter to provide Bluetooth capability to any old USB keyboard. Video after the break.

Continue reading “IPhone Becomes A Bluetooth Keyboard And Mouse”