Universal remotes are extremely convenient if they work correctly. But setting them up can be quite a hassle: often, you need to browse through long lists of TV models, key in the codes on the remote with just a blinking LED as confirmation, and then pray that the manufacturer included the correct codes for all your equipment. IR isn’t a very complicated technology, however, so it’s perfectly possible to roll your own universal remote, as [sjm4306] shows in his latest project, the Remoteduino Nano. It’s a fully programmable IR remote that gives you maximum flexibility when emulating the codes for those obscure A/V systems scattered around your home.

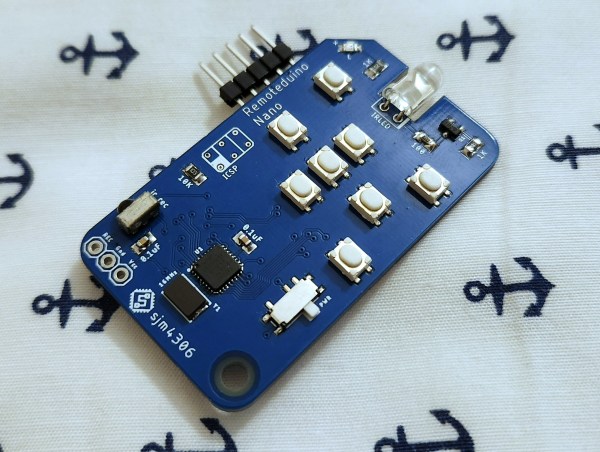

The remote runs on an ATmega328p in a tiny QFN package, which drives a standard 5 mm IR LED through a transistor. Eight buttons are available to the user, which can be freely mapped to any desired code. A five-pin header is included to program the ATmega through its serial port. However, this was mainly done to help debug – a user who only needs to program the device once would typically use a pogo-pin-based adapter instead.

Currently, codes can only be programmed through the serial port, but there’s also an IR receiver present that can be used to copy codes from an existing remote. [sjm4306] hasn’t implemented this feature in software yet, but will probably do so in a future update of the project’s Arduino sketch. If you’re impatient, you can also have a go at it yourself since all code and the board’s Gerber files are freely available for download.

Its tiny size makes the Remoteduino Nano a convenient tool to keep in your drawer if you like to tinker with A/V systems and keep losing those remotes. The Nano is actually an improved version of the original Remoteduino project that [sjm4306] developed a couple of years ago. The problem of a truly universal remote is one that dates back several decades, however.

Continue reading “The Remoteduino Nano Is A Tiny IR Remote That’s Truly Universal”