Disposable masks have been a necessity during the COVID-19 pandemic, but for all the good they’ve done, their disposal represents a monumental ecological challenge that has largely been ignored in favor of more immediate concerns. What exactly are we supposed to do with the hundreds of billions of masks that are used once or twice and then thrown away?

If the research being conducted at the University of Bristol’s Design and Manufacturing Futures Lab is any indication, at least some of those masks might get a second chance at life as a 3D printed object. Noting that the ubiquitous blue disposable mask is made up largely of polypropylene and not paper as most of us would assume, the team set out to determine if they could process the masks in such a way that they would end up with a filament that could be run through a standard 3D printer. While there’s still some fine tuning to be done, the results so far are exceptionally impressive; especially as it seems the technique is well within the means of the hobbyist.

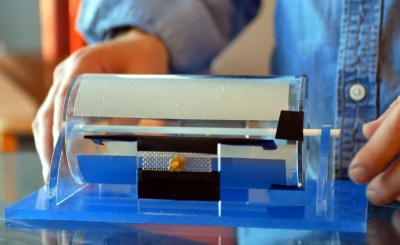

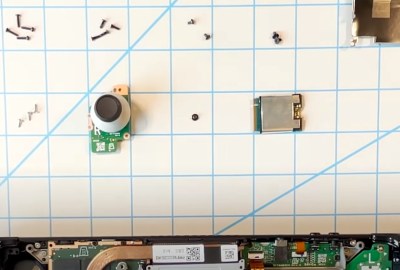

The first step in the process, beyond removing the elastic ear straps and any metal strip that might be in the nose, is to heat a stack of masks between two pieces of non-stick paper with a conventional iron. This causes the masks to melt together, and turn into a solid mass that’s much easier to work with. These congealed masks were then put through a consumer-grade blender to produce the fine polypropylene granules that’re suitable for extrusion.

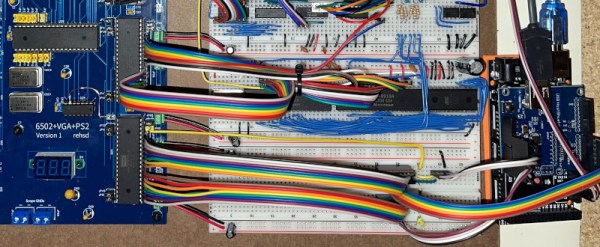

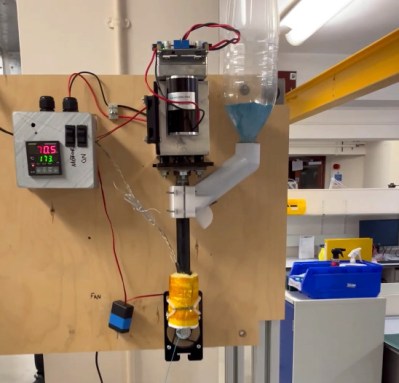

Mounted vertically, the open source Filastruder takes a hopper-full of polypropylene and extrudes it into a 1.75 mm filament. Or at least, that’s the idea. The team notes that the first test run of filament only had an average diameter of 1.5 mm, so they’re modifying the nozzle and developing a more powerful feed mechanism to get closer to the goal diameter. Even still, by cranking up the extrusion multiplier in the slicing software, the team was able to successfully print objects using the thin polypropylene filament.

This is only-during-a-pandemic recycling, and we’re very excited to see this concept developed further. The team notes that the extrusion temperature of 260 °C (500 °F) is far beyond what’s necessary to kill the COVID-19 virus, though if you planned on attempting this with used masks, we’d imagine they would need to be washed regardless. If the hacker and maker community were able to use their 3D printers to churn out personal protective equipment (PPE) in the early days of the pandemic, it seems only fitting that some of it could now be ground up and printed into something new.