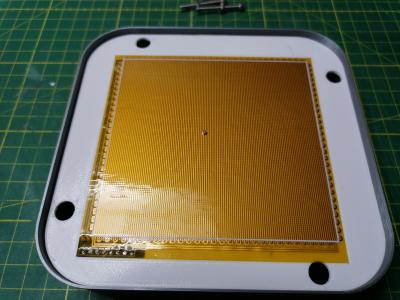

Is the Casio FX9000P a calculator or a computer? It’s hard to tell since Casio did make calculators that would run BASIC. [Menadue] didn’t know either, but since it had a CRT, a Z80, and memory modules, we think computer is a better moniker.

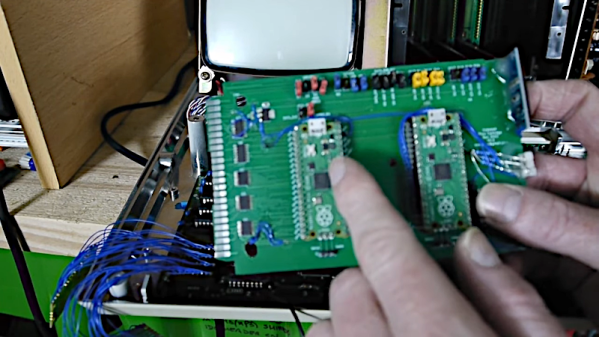

He found one of these, but as you might expect, it needed a bit of work. There were two bad video RAM chips on the device, and [Menadue] used two Raspberry Pi Picos running a program to make them think they are RAM chips. The number of wires connecting the microcontollers might raise some eyebrows, but it does appear to get the job done.

He also used more Picos to emulate memory on cartridges. Then he used a test clip and a — you guessed it — another Pico to monitor the Z80 bus signals. It is amazing that the Pico can replace what would have been state-of-the-art memory chips and a very expensive logic analyzer.

The second video mostly shows the computer in operation. The use of Picos to stand in for so much is clever. It reminded us of the minimal Z80 computer that used an Arduino for support chips. The computer itself, though, reminded us more of a cheap version of the HP9845.

Continue reading “Pi Picos Give Casio FX9000P Its Memory Back”