In the three or four decades since storing programs on audio cassettes has been relevant, a lot of irreplaceable personal computing history has been lost to the ravages of time and the sub-optimal conditions in the attics and basements where tapes have been stored. Luckily, over that time we’ve developed a lot of tools and techniques that might make it possible to recover some of these ancient treasures. But as [Noel] shows us, recovering data from cassette tapes is a tricky business.

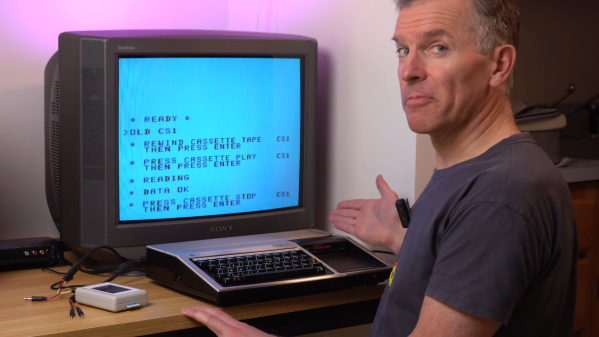

His case study for the video below is a tape from a TI-99/4A that won’t load. A quick look in Audacity at the audio waveform seems to show the problem — an area of severely attenuated signal. Unfortunately, no amount of boosting and filtering did the trick, so [Noel] had to dig a bit deeper. It turns out that the TI tape interface standard, with its redundant data structure, was somewhat to blame for the inability to read this particular tape. As [Noel] explains, each 64-bit data record is recorded to tape twice, along with a header and a checksum. If neither record decodes correctly, then tape playback just stops.

Luckily, someone who had already run into this problem spun up a Windows program to help. CS1er — our guess would be “Ceaser” — takes WAV file input and loads each record, simply flagging the bad ones instead of just bailing out. [Noel] used the program to analyze multiple recordings of the same data and eventually got enough good records to reassemble the original program, a game called Dogfight — or was it Gogfight? Either way, he managed to get most of the data off the tape, and since it was a BASIC program, it was pretty easy to figure out the missing bytes by inspection.

[Noel]’s experience will no doubt be music to the ears of the TI aficionados out there. Of which we’ve seen plenty, from the TI-99 demoscene to running Java on one, and whatever this magnificent thing is.

Continue reading “Persistence Pays In TI-99/4A Cassette Tape Data Recovery”