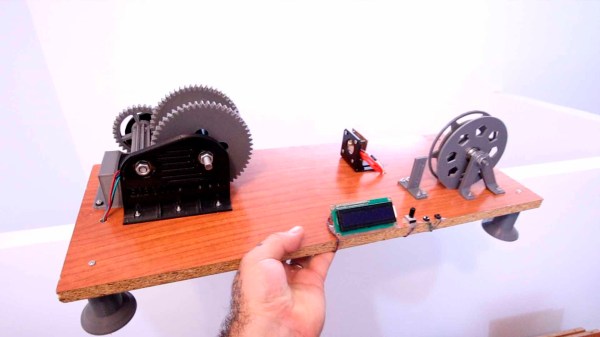

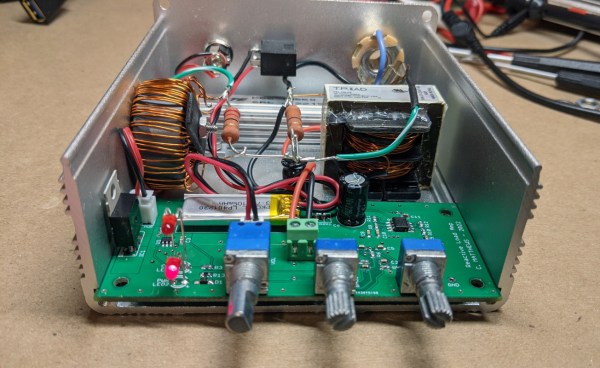

Ratcheting screwdrivers can help you work faster, even if their bulk means they’re not the best option for working in tight spaces. [ukman] decided to build a similar device of his own, relying on a slightly different mechanism — an overrunning clutch.

The design is similar to a freewheel used on a bicycle, allowing free movement in one direction while resisting it in the other. As the screwdriver is turned in one direction, the shaft is wedged by a series of cylinders that lock it in place. However, the geometric shape of the clutch allows the shaft to turn in the other direction without getting wedged in place. The result is a screwdriver that can be turned, rolled back, and turned further. Thus, screws can be tightened without loosening one’s grip on the tool.

With its 3D printed construction, it’s probably not the best tool for heavy-duty, high-torque jobs, but it looks more than capable of handling simple assembly tasks. We’ve seen some other nifty screwdrivers around these parts, too.

Continue reading “Printable One-Way Driver Skips Ratchet For A Clutch”