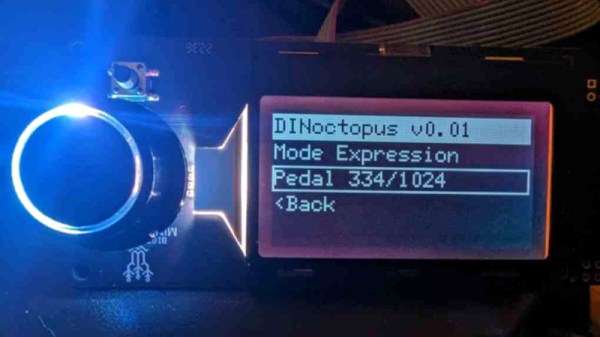

Browsing the usual websites for Chinese electronics, there are a plethora of electronic modules for almost every conceivable task. Some are made for the hobbyist or experimenter market, but many of them are modules originally designed for a particular product which can provide useful functionality elsewhere. One such module, a generic control panel for 3D printers, has caught the attention of [Bjonnh]. It contains an OLED display, a rotary encoder, and a few other goodies, and he set out to make use of it as a generic human interface board.

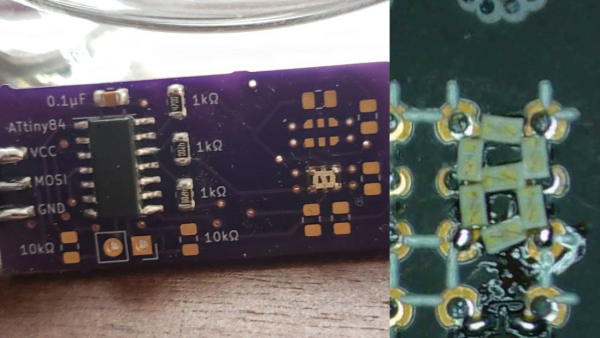

To be reverse engineered were a pair of 5-pin connectors, onto which is connected the rotary encoder and display, a push-button, a set of addressable LEDs for backlighting, a buzzer, and an SD card slot. Each function has been carefully unpicked, with example Arduino code provided. Usefully the board comes with on-board 5 V level shifting.

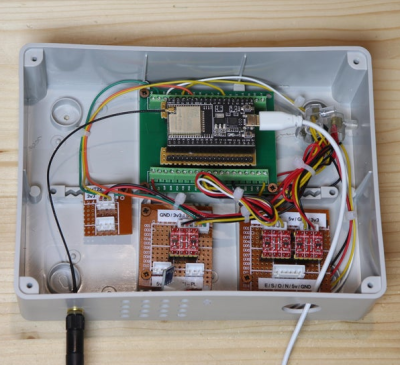

While we all like to build everything from scratch, if there’s such an assembly commonly available it makes sense to use it, especially if it’s cheap. We’re guessing this one will make its way into quite a few projects, and that can only be a good thing.