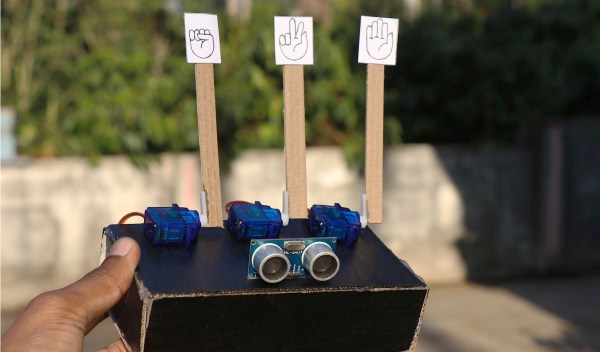

If you’re hoping that this AI-powered logic analyzer will help you quickly debug that wonky digital circuit on your bench with the magic of AI, we’re sorry to disappoint you. But if you’re in luck if you’re in the market for something to help you detect logical fallacies someone spouts in conversation. With the magic of AI, of course.

First, a quick review: logic fallacies are errors in reasoning that lead to the wrong conclusions from a set of observations. Enumerating the kinds of fallacies has become a bit of a cottage industry in this age of fake news and misinformation, to the extent that many of the common fallacies have catchy names like “Texas Sharpshooter” or “No True Scotsman”. Each fallacy has its own set of characteristics, and while it can be easy to pick some of them out, analyzing speech and finding them all is a tough job.

Continue reading “ChatGPT Powers A Different Kind Of Logic Analyzer”