With cars being essentially CAN buses on wheels, it’s no wonder that there’s a lot of juicy information about the car’s status zipping about on these buses. The main question is usually how to get access to this information, both in terms of wiring into the relevant CAN bus, and decoding the used (proprietary) protocol. Fortunately for [Alex], decoding the Volvo VIDA protocol used with his Volvo C30 was relatively straightforward, enabling the creation of a custom gauge that displays information like boost pressure and coolant temperature.

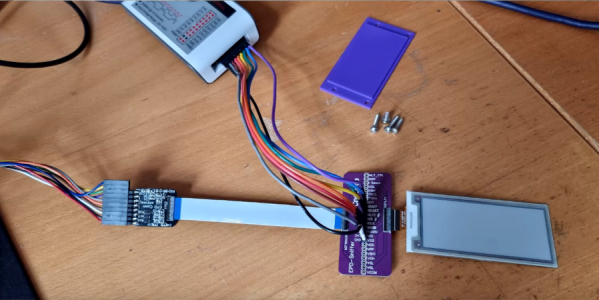

The physical interfacing is accomplished via the car’s OBD port, which conveniently provides access to the car’s two (high-speed and low-speed) CAN buses. Hardware of choice is an M2 UTH (Under the Hood) board, sporting a SAM3X Cortex-M3-based MCU, designed for permanent automotive installations. On [Alex]’s GitHub project page it is explained how the protocol works, and which bytes to look for when replicating the project.

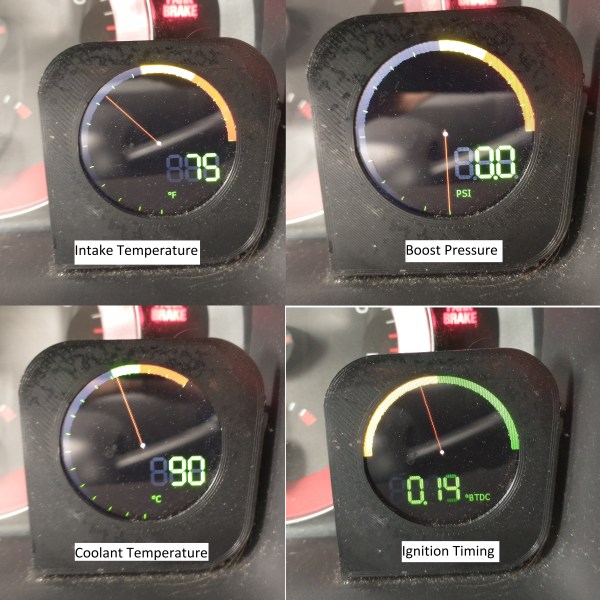

Rounding off the project is a round LCD display from 4D Systems that cycles through the status update screens. As a bonus, the dashboard illumination level is also read out in real-time, so the brightness of the display is adjusted to fit this level. All in all a well-rounded project, with interesting prospects for a more permanent integration of the gauge into the dashboard proper.

Continue reading “Volvo C30 Custom Gauge And CAN Bus Reverse Engineering”