Stored hydrogen is often touted as the ultimate green energy solution, provided the hydrogen is produced from genuinely green power sources. But there are technical problems to be overcome before your average house will be heated with pumped or tank-stored hydrogen. One problem is that the locations that have lots of scope for renewable energy, don’t always have access to plenty of pure water, and for electrolysis you do need both. A team from Melbourne University have come up with a interesting way to produce hydrogen by electrolysis directly from the air.

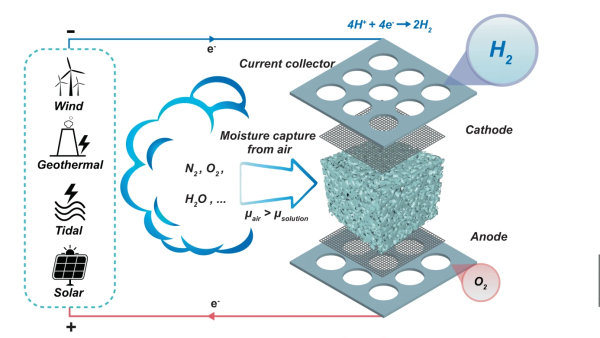

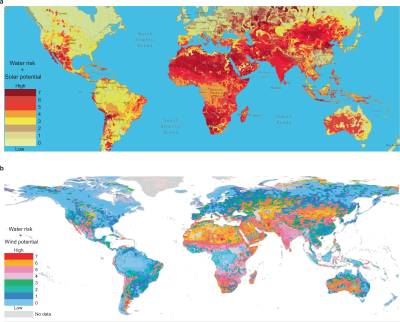

By utilising a novel electrolysis cell with a hygroscopic electrolyte, the so-called direct air electrolysis (DAE) can operate with humidity as low as 4% relative, so perfectly fine even in the most arid areas, after all there may not be clouds but the air still holds a bit of water. This is particularly relevant to regions of the world, such as deserts, where there is simultaneously a high degree of water risk, and plenty of solar potential. Direct electrolysis of saline extracted at coastal areas is one option, but dealing with the liberated chlorine is a big problem.

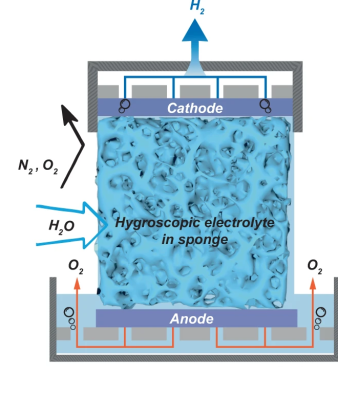

The new prototype is very simple in construction, with a sponge of melamine or a sintered glass foam soaked in a compatible electrolyte. Potassium Hydroxide (alkaline) was tried as was Potassium Acetate (base) and Sulphuric Acid, but the latter degraded the host material in a short time. Who would have imagined? Anyway, with electrolysis cell design, a key problem is ensuring the separate gasses stay separate, and in this case, are also separate from the air. This was neatly ensured by arranging the electrolyte sponge fully covered both electrodes, so as the hygroscopic material extracted water from the air, the micro-channels in the structure filled up with liquid, with it touching both ends of the cell, forming the circuit and allowing the electrolysis to proceed.

sponge fully covered both electrodes, so as the hygroscopic material extracted water from the air, the micro-channels in the structure filled up with liquid, with it touching both ends of the cell, forming the circuit and allowing the electrolysis to proceed.

Hydrogen, being very light, would rise upward through holes in the cathode, to be collected and stored. Oxygen simply passed back into the air, after passing though the liquid reservoir at the base. Super simple, and from reading the paper, quite effective too.

You can kind of imagine a future built around this now, where you’re driving your hydrogen fuel cell powered dune buggy around the Sahara one weekend, and you stop at a solar-powered hydrogen fuel station for a top up and a pasty. Ok, possibly not that last bit.

The promised hydrogen economy may be inching closer. We covered using aluminium nanoparticles to rip hydrogen out of water. But once you have the gas, you need to store and handle it. Toyota might have a plan for that. Then perhaps handling gas directly at all isn’t a great idea, and maybe the future is paste?

Thanks to [MmmDee] for the tip!