Imagine a movie featuring a scene set in a top-secret bioweapons research lab. The villain, clad in a bunny suit, strides into the inner sanctum of the facility — one of the biosafety rooms where only the most infectious and deadliest microorganisms are handled. Tension mounts as he pulls out his phone; surely he’ll use it to affect some dramatic hack, or perhaps set off an explosive device. Instead, he calls up his playlist and… plays a song? What kind of villain is this?

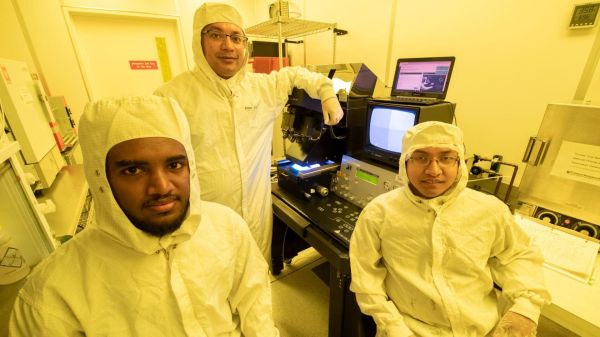

As it turns out, perhaps one who has read a new paper on the potential for hacking biosafety rooms using music. The work was done by University of California Irvine researchers [Anomadarshi Barua], [Yonatan Gizachew Achamyeleh], and [Mohammad Abdullah Al Faruque], and focuses on the negative pressure rooms found in all sorts of facilities, but are of particular concern where they are used to prevent pathogens from escaping into the world at large. Continue reading “Sick Beats: Using Music And Smartphone To Attack A Biosafety Room”