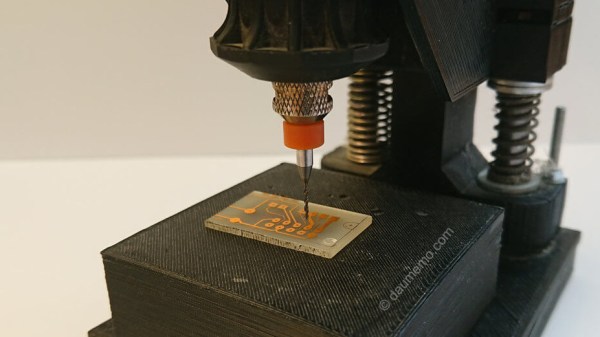

When shooting video, an easy way to get buttery smooth panning and tracking is to use a mechanical device like a rail to literally slide the camera side to side. These range from what is essentially a skateboard to incredible programmable multi-axis industrial robots, a wide variety of which have been visible in the backgrounds of Youtuber’s sets for years. But even the “low end” devices can run hundreds of dollars (all that anodized aluminum doesn’t come cheap!). Edelkrone has been building lust worthy professional (read, pricey) motion setups for a decade. But in the last year they’ve started something pretty unusual; lowering prices with their Ortak series of 3D printed equipment. But this time, you do the printing.

Since the RepRap we’ve been excited about the future of democratized at home manufacturing, but to a large extent that dream hasn’t materialized. Printers are much more useful now than in the early days but you can’t buy a new mug from Starbucks and print it at home. But maybe that’s changing with Edelkrone’s offering.

When you buy an Ortak product you get one thing: all the fasteners and hardware. So the final product is more durable and appears more finished than what would pop out of your Prusa unaided. What about the rest of the device? That’s free. Seriously. Edelkrone freely provides STLs (including print setting recommendations) with detailed step-by-step assembly instructions and videos (sample after the break). Nice hack to avoid piracy, isn’t it?

Why choose the do-it-at-home style product? A significant price reduction of course! The Ortak line currently includes two products, the FlexTILT head you see above, and a skateboard-style slide called the SKATER 3D. Both of these were sold fully finished before making it to the DIY scene. The FlexTILT Head 2 comes in at $149 when you buy it whole. And when the PocketSKATER 2 was for sale, it included a FlexTILT Head and came to $249. Now? Each hardware kit is just $29.

So is this it? Have we hit the artisanal DIY micro-manufactured utopian dream? Not yet, but maybe we’re a little closer. Edelkrone is a real company which is really selling these as products, right there on their website along with everything else. They refer to it as “co-manufacturing” which we think is a clever name, and talk about expanding the program to include electronics. We can’t wait to see how the experiment goes!

Continue reading “Pan And Tilt To A New 3D Printed Business Model”