We don’t have to tell you that the current mobile phone market is a bit bleak for folks who value things like privacy, security, and open source. While there have been a few notable attempts to change things up, from phone-optimized versions of popular Linux distributions to the promise of modular handsets — we still find ourselves left with largely identical slabs released by a handful of companies which often seem to treat the customer as a product.

Instead of waiting for technological relief that may never come, [vrhelmutt] has decided to take matters into their own hands by looking to the past. Specifically, by embracing the relatively uncommon Nokia Asha 210. Released in 2013, this so-called “feature phone” offers a full QWERTY keyboard, Nokia’s Series 40 operating system, WiFi, Bluetooth, and a removable BL-4U battery. Unfortunately, with 2G cellular networks quickly being shut down, it’s not likely to get a signal for much longer (if at all, depending on where you live).

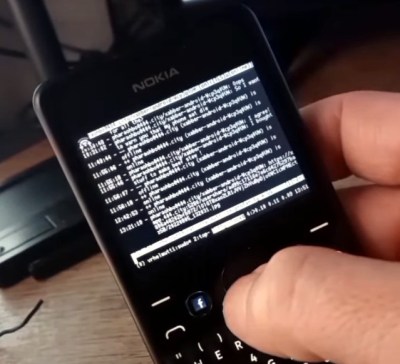

So why would you want to use some weird old Nokia phone in 2022? [vrhelmutt] argues that there’s a whole world of S40 software out there that can still be put to use, ranging from games to SSH clients. It’s also relatively easy to develop your own S40 applications in Java, with the original software development kit still freely available online. Combined with the solid (if considerably dated) hardware, this makes the Nokia Asha 210 a surprisingly compelling choice for a pocket hacking platform.

So why would you want to use some weird old Nokia phone in 2022? [vrhelmutt] argues that there’s a whole world of S40 software out there that can still be put to use, ranging from games to SSH clients. It’s also relatively easy to develop your own S40 applications in Java, with the original software development kit still freely available online. Combined with the solid (if considerably dated) hardware, this makes the Nokia Asha 210 a surprisingly compelling choice for a pocket hacking platform.

Whether you’re looking for a cheap device that will let you chat on IRC from your couch, or want to write your own custom software for controlling your home automation or robotics projects, you might want to check the second-hand market for a Nokia Asha 210. Or if you’re eager to get experimenting immediately, [vrhelmutt] is actually selling these phones pre-loaded with a wide array of games and programs. Don’t consider this to be an official endorsement; frankly we’re not feeling too confident about the legality of redistributing all this software, but at least it’s an option for those looking to get off the modern smartphone thrill-ride.

If you’re looking for something even farther removed from today’s mobile supercomputers, perhaps we could interest you in the Rotary Un-Smartphone.

Continue reading “Finding Digital Solace In An Old Nokia Phone”