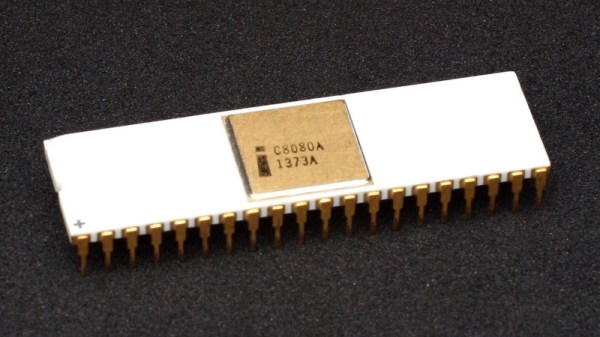

The early history of microprocessors is a surprisingly complex one, with more than one claimant for the prize of being the first, and multiple competing families. That the first commercially available part was the Intel 4004 is a matter of record, but it’s fair to say that few of us will have ever encountered one. Even its 8-bit sibling the 8008 would not have featured heavily in a 1974 version of Hackaday, such was its exotic nature. If there’s a microprocessor that can be claimed to have started it all for us then, it’s the Intel 8080. It established the 8-bit microporcessor with an 8-bit bus and a 16-bit address space, it had an order of maginitude more performance than its predecessors, and crucially it would become affordable enough for experimenters. It provided the guts of the MITS Altair 8800 microcomputer, and thus kickstarted the progression of home computers which led to the devices you use every day.

The 8080 is in our sights today, thanks to [DeviceGuru], who was sent down memory lane by thoughts of the 6502-based KIM-1 from his master’s thesis project. This led to memories of the 8080 Abie computer that he built for himself in 1979, for which he provides us some details and hand-drawn schematics. By then the 8080’s need for several support chips made it somewhat outdated, but from his perspective the chip could be had from Radio Shack without too much outlay. His tale of hand-assembling 8080 code and sending it to a friend for blowing onto a PROM might be familiar to some readers of a certain age.

Though the 8080 ceased volume production a quarter century ago (surprisingly there are still places you can get a new one though) it hasn’t entirely disappeared from our community’s consciousness. [DeviceGuru] tells us about the 8080 Microprocessor kit from [Wichit Sirichote] in Thailand which is a single board computer in the 1970s vein, hex keypad and all.

As you might expect, the 8080 hasn’t appeared in many projects here due to its rarity. Those that have seem more likely to feature its Eastern Bloc clones, such as this Polish model or this Russian one. It’s worth the reminder that if you fancy exploring some 8080 code of your own that you don’t even need an 8080 to run it on some silicon. The hugely popular Zilog Z80 as found in retrocomputers such as the RC2014 is fully mostly 8080 code compatible, indeed some of us learned about microprocessors that way because 8080 books were discounted in 1983 and Z80 ones weren’t.

Header image: Konstantin Lanzet [CC BY-SA 3.0].