Is it ironic when a YouTube channel named “The Current Source” needs to build a current source? Or is that not ironic and actually just coincidental?

Regardless of linguistic considerations, [Derek], proprietor of the aforementioned channel has made and disassembled a few current sources in his day. Most of those jobs were for one-off precision measurements or even to drive a string of LEDs in what he describes as a pair of migraine-inducing glasses. Thankfully, The junk box current source presented in the video below is more in service of the former than the latter, as his goal is to measure very small resistances in semiconductors using Kelvin clips.

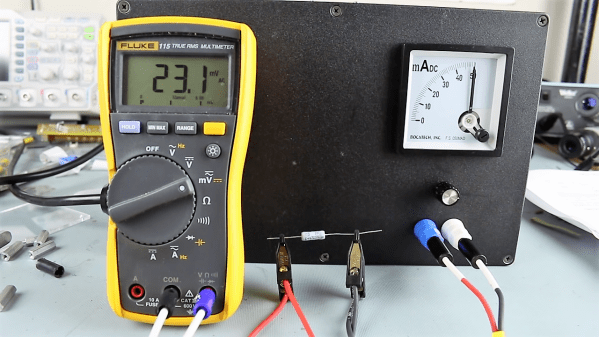

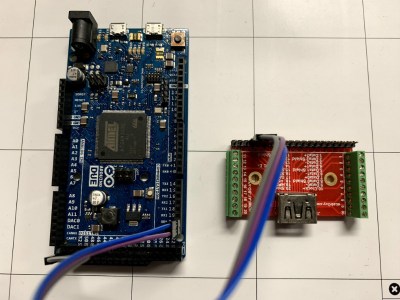

The current source uses a 24-volt switch-mode power supply and the popular LM317 adjustable voltage regulator. The ‘317 can be configured in a constant current mode by connecting the chip’s adjustment pin to the output through a series resistance. A multiturn pot provides current adjustment, although the logarithmic taper is not exactly optimal for the application. We spotted a pair of what appear to be optoisolators in the build too, but there’s no schematic and no discussion of what they do. [Derek] puts the final product to use for a Kelvin measurement of a 0.47-Ω 1% resistor at the end of the video.

We’re glad to see [Derek] in action; you may recall his earlier video about measuring his own radiation with a Geiger counter after treatment for thyroid cancer. Here’s hoping that’s behind him now.

Continue reading “Junkbox Constant Current Source Helps With Kelvin Sensing”

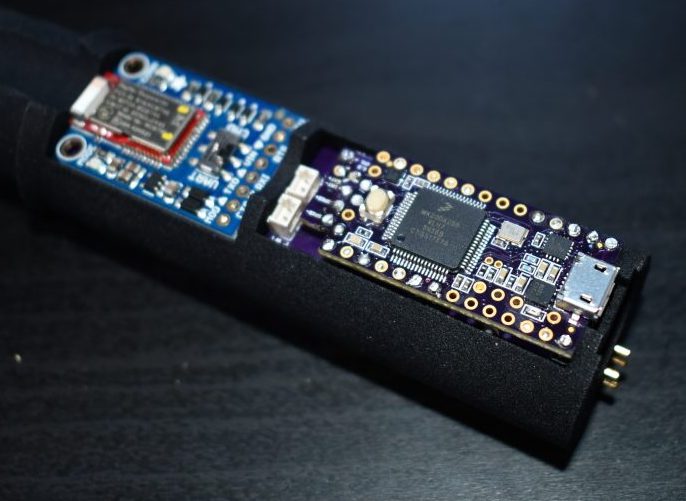

The hilt is filled with an assembly of 18650’s and a Teensy mounted with a custom shield, all fit inside a printed midframe. The whole build is all about robust design that’s easy to assemble. The main board is book-ended by perpendicular PCBs mounted to the ends, one at the top to connect to the blade and one at the bottom to connect to a speaker. Towards the bottom there is space for an optional Bluetooth radio to allow remote RGB control.

The hilt is filled with an assembly of 18650’s and a Teensy mounted with a custom shield, all fit inside a printed midframe. The whole build is all about robust design that’s easy to assemble. The main board is book-ended by perpendicular PCBs mounted to the ends, one at the top to connect to the blade and one at the bottom to connect to a speaker. Towards the bottom there is space for an optional Bluetooth radio to allow remote RGB control.