Battlelines are being drawn in Canada over the lowly Flipper Zero, a device seen by some as an existential threat to motor vehicle owners across the Great White North. The story started a month or so ago, when someone in the government floated the idea of banning devices that could be “used to steal vehicles by copying the wireless signals for remote keyless entry.” The Flipper Zero was singled out as an example of such a nefarious device, even though relatively few vehicles on the road today can be boosted using the simple replay attack that a Flipper is capable of, and the ones that are vulnerable to this attack aren’t all that desirable — apologies to the 1993 Camry, of course. With that threat hanging in the air, the folks over at Flipper Devices started a Change.org petition to educate people about the misperceptions surrounding the Flipper Zero’s capabilities, and to urge the Canadian government to reconsider their position on devices intended to explore the RF spectrum. That last bit is important, since transmit-capable SDR devices like the HackRF could fall afoul of a broad interpretation of the proposed ban; heck, even a receive-only SDR dongle might be construed as a restricted device. We’re generally not much for petitions, but this case might represent an exception. “First they came for the Flipper Zero, but I did nothing because I don’t have a Flipper Zero…”

movie21 Articles

Re-Inventing The Single 8 Home Movie Format

[Jenny List] has been reverse-engineering and redesigning the Single8 home movie film cartridge for the modern age, to breathe life into abandoned cine cameras.

One of the frustrating things about working with technologies that have been with us for a while is the proliferation of standards and the way that once-popular formats can become obsolete over time. This can leave equipment effectively unusable and unloved.

There is perhaps no greater example of this than in film photography – an industry and hobby that has been with us for over 100 years and that has left many cameras orphaned once the film format they relied on was no longer available (Disc film, anyone?).

Thankfully, Hackaday’s own [Jenny List] has been working hard to bring one particular cine film format back from the dead and has just released the fourth instalment in a video series documenting the process of resurrecting the Single8 format cartridge. Continue reading “Re-Inventing The Single 8 Home Movie Format”

Every Frame A Work Of Art With This Color Ultra-Slow Movie Player

One of the more recent trendy builds we’ve seen is the slow-motion movie player. We love them — displaying one frame for a couple of hours to perhaps a full day is like an ever-changing, slowly morphing work of art. Given that most of them use monochrome e-paper displays, they’re especially suited for old black-and-white films, which somehow makes them even more classy and artsy.

But not every film works on a monochrome display. That’s where this full-color ultra-slow motion movie player by [likeablob] shines. OK, full color might be pushing it a bit; the build centers around a 5.65″ seven-color EPD module. But from what we can see, the display does a pretty good job at rendering frames from films like Spirited Away and The Matrix. Of course there is the problem of the long refresh time of the display, which can be more than 30 seconds, but with a frame rate of one every two hours, that’s not a huge problem. Power management, however, can be an issue, but [likeablob] leveraged the low-power co-processor on an ESP32 to handle the refresh tasks. The result is an estimated full year of battery life for the display.

We’ve seen that same Waveshare display used in a similar player before, and while some will no doubt object to the muted color rendering, we think it could work well with a lot of movies. And we still love the monochrome players we’ve seen, too.

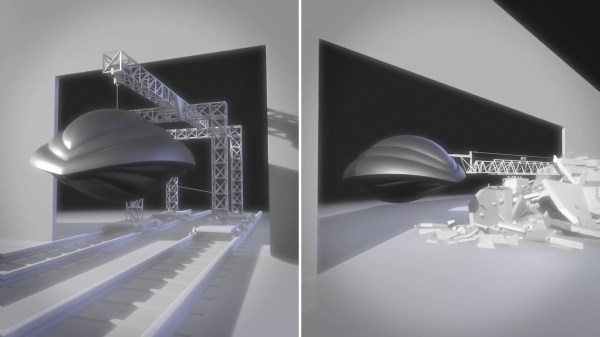

Obsessively Explaining The Visual Effects In Flight Of The Navigator

[Captain Disillusion] has earned a reputation on YouTube for debunking hoaxes and spreading a healthy sense of skepticism while having some of the highest production value on the platform and pretending to be some kind of inter-dimensional superhero. You’ve likely seen him give a careful explanation of how some viral video was faked alongside a generous dose of sarcastic humor and his own impressive visual effects. VFXcool is a series on his channel that takes deep dives into movies that are historically significant in the effects industry. For this installment, [Captain Disillusion]’s “intern”, [Alan], takes over to breakdown how filmmakers brought a futuristic spaceship to life in 1986’s Flight of the Navigator.

Making a movie requires hacks upon hacks, and that goes double in the era when the technology and techniques we now take for granted were being developed even as they were being put to film. The range of topics covered here is extreme: from full-scale props to models; from robotic motion control rigs to stop motion animation; from early computer graphics to the convoluted optical compositing that was necessary before digital workflows were possible. The tools themselves may be outdated, but understanding the history and the processes allows for a deeper insight into how we accomplish these kinds of effects today. And, really, it’s just so… cool.

[Captain Disillusion]’s previous VFXcool is all about the Back to the Future trilogy, and it’s a little shorter with more information on motion control rigs. We also love seeing how people make DIY effects in their own homes. LEGO actually seems like a pretty popular option for putting together whole scenes in amateur filmmaking.

Continue reading “Obsessively Explaining The Visual Effects In Flight Of The Navigator“

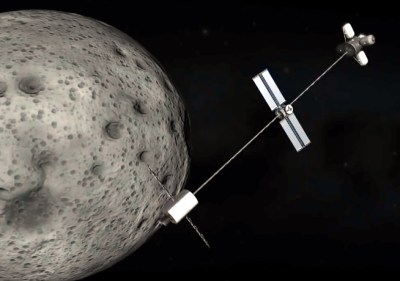

Kerbal Space Program Goes To The Movies In Stowaway

Fans of the lusciously voiced space aficionado [Scott Manley] will know he often uses Kerbal Space Program (KSP) in his videos to knock together simple demonstrations of blindingly complex topics such as orbital mechanics. But as revealed in one of his recent videos, YouTube isn’t the only place where his KSP craft can be found these days. It turns out he used his virtual rocket building skills to help the creators of Netflix’s Stowaway develop a realistic portrayal of a crewed spacecraft in a Mars cycler orbit.

The Mars cycler concept was proposed in 1985 by Buzz Aldrin as a way to establish a long-term human presence on the Red Planet. Put simply, it describes an orbit that would allow a vehicle to travel continuously between Earth and Mars while needing only an occasional engine burn for course corrections. The spacecraft couldn’t actually stop at either planet, but while it made a close pass, smaller craft could rendezvous with it to hitch a ride. The concept can be thought of as a sort of interplanetary train: where passengers and cargo are picked up and dropped off at “stations” above Earth and Mars. It’s worth noting that a similar cycler orbit should be possible for Earth-Venus trips, but nobody really wants to go there.

The writers of Stowaway wanted their film to take place on a Mars cycler, and to avoid having to create the illusion of weightlessness, they wanted their fictional craft to also have some kind of artificial gravity. The only problem was, they weren’t sure what that would actually look like. So they reached out to [Scott], who in turn used KSP to throw together a rough idea of how such a ship might work in the real-world.

As you can see in the video below, the CGI spacecraft shown in the film’s recently released trailer ended up bearing a strong resemblance to its KSP prototype. While naturally some artistic license was used, [Scott] is excited by what he’s seen so far. The spinning spacecraft, which uses a spent upper stage to counterbalance its crew module and features a stationery utility node at the center, certainly looks impressive; all the more so with the knowledge that it’s based on sound principles.

While Netflix has had a hand in some surprisingly realistic science fiction in the past, they’ve also greenlit some real groan-worthy productions (if you haven’t watched Away, don’t). So until we can see the whole thing for ourselves, we can only hope that [Scott]’s sage advice will allow the crew of Stowaway to fly safe.

Continue reading “Kerbal Space Program Goes To The Movies In Stowaway“

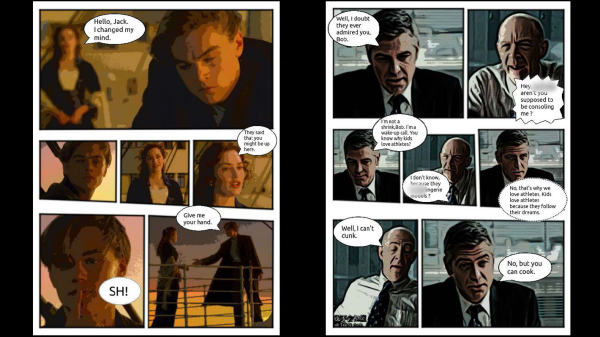

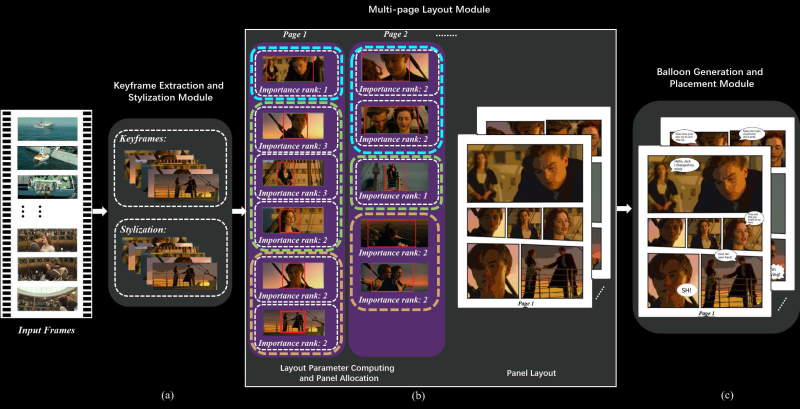

Read Your Movies As Automatically Generated Comic Books

A research paper from Dalian University of Technology in China and City University of Hong Kong (direct PDF link) outlines a system that automatically generates comic books from videos. But how can an algorithm boil down video scenes to appropriately reflect the gravity of the scene in a still image? This impressive feat is accomplished by saving two still images per second, then segments the frames into scenes through analysis of region-of-interest and importance ranking.

For its next trick, speech for each scene is processed by combining subtitle information with the audio track of the video. The audio is analyzed for emotion to determine the appropriate speech bubble type and size of the subtitle text. Frames are even analyzed to establish which person is speaking for proper placement of the bubbles. It can then create layouts of the keyframes, determining panel sizes for each page based on the region-of-interest analysis.

The process is completed by stylizing the keyframes with flat color through quantization, for that classic cel shading look, and then populating the layouts with each frame and word balloon.

The team conducted a study with 40 users, pitting their results against previous techniques which require more human intervention and still besting them in every measure. Like any great superhero, the team still sees room for improvement. In the future, they would like to improve the accuracy of keyframe selection and propose using a neural network to do so.

Thanks to [Qes] for the tip!

Movie Magic Hack Chat

Join us on Wednesday, January 20th at noon Pacific for the Movie Magic Hack Chat with Alan McFarland!

If they were magically transported ahead in time, the moviegoers of the past would likely not know what to make of our modern CGI-driven epics, with physically impossible feats performed in landscapes that never existed. But for as computationally complex as movies have become, it’s the rare film that doesn’t still need at least some old-school movie magic, like hand props, physical models, and other practical effects.

To make their vision come to life, especially in science fiction films, filmmakers turn to artists who specialize in practical effects. We’ve all seen their work, which in many cases involves turning ordinary household objects into yet-to-be-invented technology, or creating scale models of spaceships and alien landscapes. But to really sell these effects, adding a dash of electronics can really make the difference.

Enter Alan McFarland, an electronics designer and engineer for the film industry. With a background in cinematography, electronics, and embedded systems, he has been able to produce effects in movies we’ve all seen. He designed electroluminescent wearables for Tron: Legacy, built the lighting system for the miniature Fhloston Paradise in The Fifth Element, and worked on the Borg costumes for Star Trek: First Contact. He has tons of experience making the imaginary look real, and he’ll join us on the Hack Chat to discuss the tricks he keeps in his practical effects toolkit to make movie magic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e13S0SenmPQ

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, January 20 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, January 20 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io. You don’t have to wait until Wednesday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.