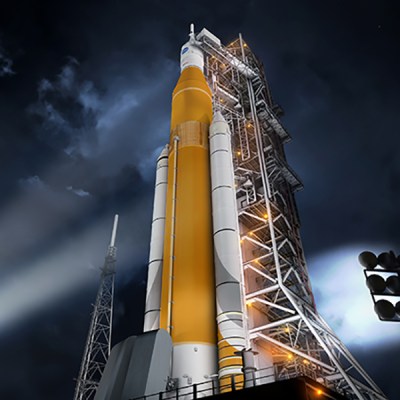

Things aren’t looking good for NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS). Occasionally referred to as the “Senate Launch System”, or even less graciously, the “Rocket to Nowhere”, the super heavy-lift booster has long been a bone of contention for those in the industry. Designed as an evolution of core Space Shuttle technology, the SLS promised to reuse existing infrastructure to deliver higher payload capacities and lower operating costs than its infamous winged predecessor. But in the face of increased competition from commercial launch providers and proposed budget cuts targeting future upgrades and expansions of the core booster, the significantly over budget and behind schedule program is in a very precarious position.

Which is not to say the SLS doesn’t look impressive, at least on paper. In its initial configuration it would easily take the title as the world’s most powerful rocket, capable of lifting nearly 105 tons into low Earth orbit (LEO), compared to 70 tons for SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. It would still fall short of the mighty Saturn V’s 155 tons to LEO, but the proposed “Block 2” upgrades would increase SLS payload capability to within striking distance of the iconic Apollo-era booster at 145 tons. Since the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, NASA has been adamant that the might of SLS was the only way the agency could accomplish bigger and more ambitious missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Which is not to say the SLS doesn’t look impressive, at least on paper. In its initial configuration it would easily take the title as the world’s most powerful rocket, capable of lifting nearly 105 tons into low Earth orbit (LEO), compared to 70 tons for SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy. It would still fall short of the mighty Saturn V’s 155 tons to LEO, but the proposed “Block 2” upgrades would increase SLS payload capability to within striking distance of the iconic Apollo-era booster at 145 tons. Since the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, NASA has been adamant that the might of SLS was the only way the agency could accomplish bigger and more ambitious missions to the Moon, Mars, and beyond.

Or at least, they were. On March 13th, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine testified to Congress that in an effort to avoid further delays, the agency is exploring the possibility of sending their Orion spacecraft to the Moon with a commercial launcher. The statement came as a shock to many in the aerospace community, as it would seem to call into question the future of the entire SLS program. If commercial rockets can do the job of SLS, at least in some cases, why does the agency need it?

NASA is currently preparing a report which investigates what physical and logistical modifications would need to be made to missions originally slated to fly on SLS; a document which is sure to be scrutinized by SLS supporters and critics alike. Until the report is released, we can speculate about what this hypothetical flight to the Moon might look like.

Continue reading “Could Orion Ride Falcon Heavy To The Moon?”