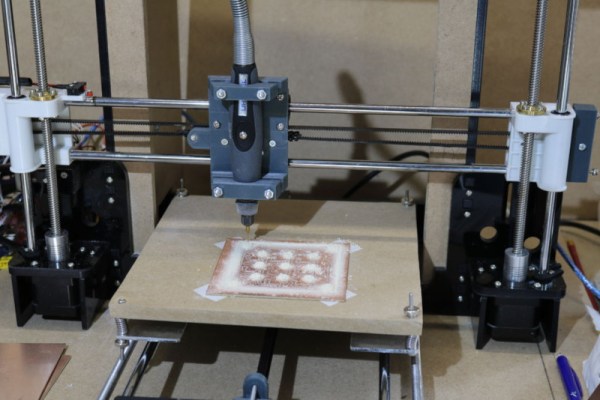

Got a 3D printer? With a bit of work, you may also have a PCB miller. That’s the basis of this neat hack by [Gosse Adema], who converted an Anet A8 3D printer into a PCB miller by building a holder for a Dremel rotary tool and adapting the GCode. This approach means that the adaptations to the printer are minimal: the only hardware is a 3D-printed holder for the Dremel that replaces the print head. The result is an impressive PCB milling machine that can do double-sided PCBs and make through holes.

The excellent write-up that [Gosse] did on this hack describes how he converted the printer, and how he took an EagleCAD design and converted it into four GCode files. That’s one for each side of the PCB, one for through holes and one for the final outline of the PCB. These are then fed to the 3D printer and cut in turn with an appropriate milling bit on the Dremel.

We’ve featured a few similar conversions before, such as this vintage conversion of a Makerbot and this cheap engraver conversion, but this one is much more detailed than those, covering the entire process from PCB design to final product.