The Hackaday Superconference is all about showcasing the hardware heroics of the Hackaday community. We also have a peer-reviewed journal with the same goal, and for the 2018 Hackaday Superconference we got a taste of the first paper to make it into our fully Open Access Journal. It comes from Ted Yapo, it is indeed a tale of hardware heroics: what happens when you don’t want to spend sixty thousand dollars on a vector network analyzer?

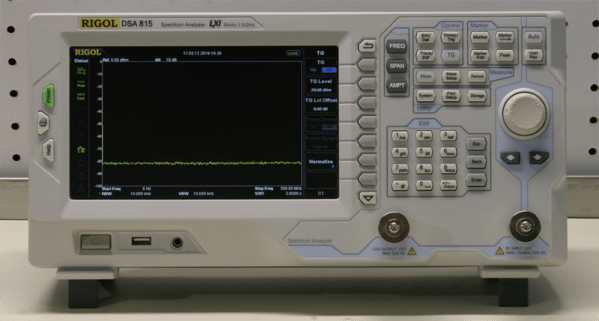

Ted’s talk begins with a need for a network analyzer. These allow for RF measurements, but if you ever need one, be prepared: you can spend twenty thousand dollars on a used VNA. Around the time Ted’s project began, Rigol released their cheap spectrum analyzer, the DSA815. This thing only cost a thousand dollars. It was their first revision of the hardware, and it was only a scalar network analyzer. Being the first revision of the hardware, there were a few problems; there was leakage that would affect the measurement. The noise floor was higher than it should have been. These problems can be corrected, though, with a little bit of cunning from Ted:

Continue reading “How To Deal With A Cheap Spectrum Analyzer”