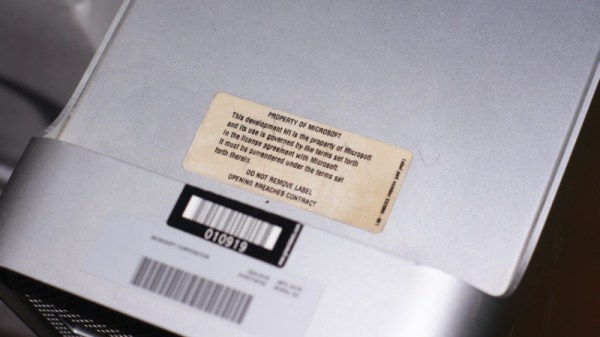

The original Xbox launched way back in 2001, to much fanfare. This was Microsoft’s big first entry into the console market, with a machine packing a Pentium III CPU, and commodity PC hardware, contributing significantly to its bulk. Modding was a major part of the early Xbox scene, and as the original hardware has grown too feeble to keep up with modern tasks, enterprising makers have instead turned to packing the black box with modern hardware. The team at [Linus Tech Tips] decided that other builds out there weren’t serious enough, and decided to take things up a notch.

The build starts with a passively cooled compact power supply, a Core i5 8400 6-core CPU, and a GeForce RTX2070 to handle graphical tasks. Parts were carefully selected for a combination of performance, packaging, and with an eye to the thermal limits inherent in stuffing high-powered modern hardware into a tight Xbox shell.

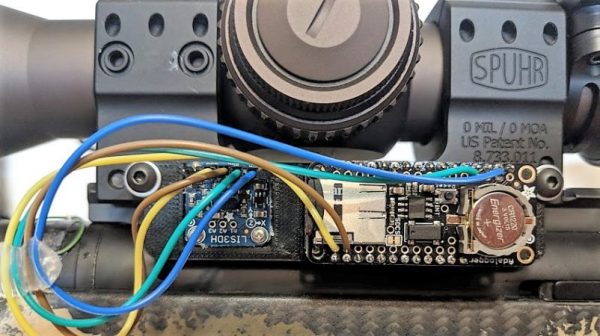

All manner of oddball techniques are used to make the build happen. The GPU is connected through a PCI Express cable, which we were surprised to learn was a thing, given the nature of high-speed signals and long transmission lines. The Xbox shell had its original metal insert and plastic standoffs removed, with an aluminium inner shell being CNC cut and bent up on a pan brake to act as a new internal chassis. There’s yet more carnage to come, as the GPU has its extraneous DVI port hacked off with a grinding wheel.

In the end, after much cutting and cajoling, the parts come together and fit inside the case, making the sleeper build a reality. It’s fun to watch the team fiddle with config files and struggle to load and play local multiplayer games, as they realise that there are just some things that consoles do better.

Regardless, it’s an impressive casemod that goes to show what you can pull off with some off-the-shelf parts, a well-stocked workshop, and some ingenuity. If you’re looking for more case mod inspiration, try out this all-in-one printer build. Video after the break.

[Thanks to Keith O for the tip!]

Continue reading “Original Xbox Gets Hardware Transplant, And Is Very Fast”