Storing electrical energy is a huge problem. A lot of gear we use every day use some form of battery and despite a few false starts at fuel cells, that isn’t likely to change any time soon. However, batteries or other forms of storage are important in many alternate energy schemes. Solar cells don’t produce when it is dark. Windmills only produce when the wind blows. So you need a way to store excess energy to use for the periods when you aren’t creating electricity. [Kris De Decker] has an interesting proposal: store energy using compressed air.

Compressed air storage is not a new idea. On a large scale, there have been examples of air compressed in underground caverns and then released to run a turbine at a future date. However, the efficiency of this is poor — around 40 to 50 percent — mainly because the air heats up during compression and often needs to be prewarmed (using energy from another source) prior to decompression to prevent freezing. By comparison, batteries can be 70 to 90 percent efficient, although they have their own problems, too.

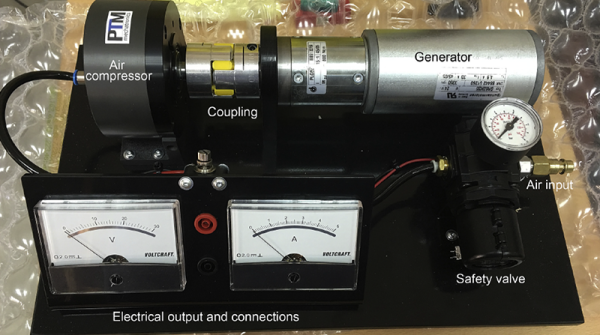

The idea explored in this paper is not to try to store a power plant’s worth of energy in a giant underground cavern, but rather use smaller compressed air setups like you would use batteries to store power at the point of consumption. The technology is called micro-CAES (an acronym for compressed air energy storage).