To those of us in the corporate world, the conference room is where hope goes to die. Crammed into a space too small for the number of invitees, the room soon glows with radiated body heat and the aromas of humans as the time from their last shower gradually increases. To say it’s not a recipe for productivity is an understatement at best.

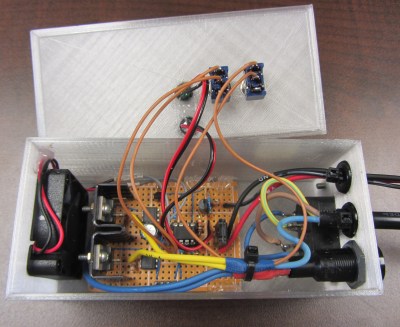

Having suffered through too many of these soporific situations, [Charles Ouweland] took matters into his own hands and built this portable air quality meter for meetings. With an OLED display on top and sensors inside, it displays not only the temperature, humidity, and barometric pressure, but also the CO₂ concentration and the levels of volatile organic compounds (VOC), noxious substances sometimes off-gassed from building materials, furniture upholstery, and coworkers alike.

The monitor quantifies his meeting misery, which we’re sure wins him points with his colleagues. For our part, though, what we find interesting is his design process. He started where many of us would, with an Arduino Uno. The sensor modules, a CCS811 for VOC and CO₂ as well as a BME280 for temperature, humidity, and pressure, both needed 3.3 volts, so he added a regulator to knock the Arduino’s 5-volt supply into range and some MOSFETs for level matching. Things were getting bulky, though, so he set about reducing the component count. The Uno went by stripping out its already programmed MCU. That killed the need for the regulator and MOSFETs, since everything would be happy with 3.3 volts. A few more rounds of optimization led to the final product, compact enough to run on a pair of AA batteries.

This is a great lesson in going from prototype to product. And it’s so compact, it could even ride on top of a Roomba to map the conference room’s floor-level air quality.