One of the most common ways of measuring the speed of a vehicle is by using radar, which typically involves generating radio waves, directing them at a moving vehicle, and measuring the various ways that they return to the device. This is a tried-and-true method, but can be expensive and technically complex. [GeeDub] wanted an easier way of measuring vehicles passing by his home, so he switched to using sonar instead to measure speeds based on the sounds the cars generate themselves.

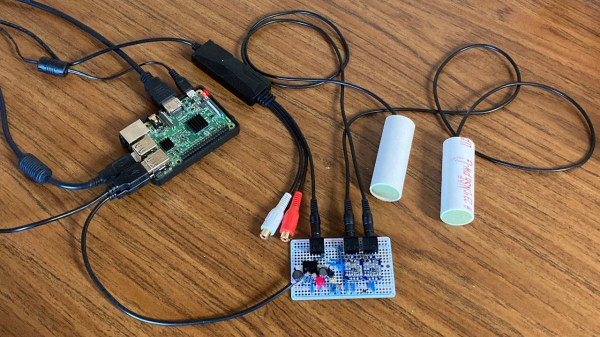

The method he is using is similar to passive sonar in submarines, which can locate objects underwater based on the sounds they produce. After a false start attempting to measure Doppler shift, he switched to time correlation using two microphones, essentially using stereo audio input to detect subtle differences in arrival times of various sounds to detect the positions of passing vehicles. Doing this fast enough and extrapolating the data gathered, speed information can be calculated. For the data gathering and calculation, [GeeDub] is using a Raspberry Pi to help keep costs down, and some further configuration of the microphones and their power supplies were also needed to ensure quality audio was gathered.

With the system in place in a window, it detected around 9,000 vehicles over a three-day period. The software generates a normal distribution of vehicle speeds for this time, with the distribution centered on around 35 MPH, slightly above the posted speed limit of 30. As long as there’s a clear line of sight to the road using this system it’s just as effective as some other passive systems we’ve seen to measure vehicle speed. Of course, active speed measurement systems are not out of the realm of possibility if you’re willing to spend a little more.