Over the years, E3D has made a name for themselves as a manufacturer of very high-quality hotends for 3D printers and other printer ephemera. One of their more successful products is the Titan Extruder, a compact extruder for 3D printers that is mostly injection-molded plastic. The front piece of the Titan is a block of molded polycarbonate, a plastic that simply shouldn’t fail in its normal application of holding a few gears and bearings together. However, a few months back, reports of cracked polycarbonate started streaming in. This shouldn’t have happened, and necessitated a deep dive into the failure analysis of these extruders. Lucky for us, E3D is very good at doing engineering teardowns. The results of the BearingGate investigation are out, and it’s a lesson we can all learn from.

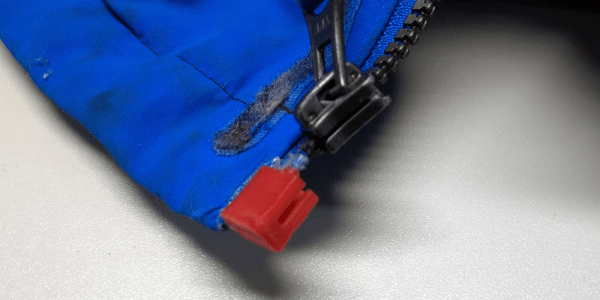

The first evidence of a problem with the Titan extruders came from users who reported cracking in the polycarbonate case where the bearing sits. The first suspect was incorrectly manufactured polycarbonate, perhaps an extruder that wasn’t purged, or an incorrect resin formulation during manufacturing. A few whacks with a hammer of each production run ruled out that possibility, so suspicion turned to the bearing itself.

After a few tests with various bearings, the culprit was found: in some of the bearings, the lubricant mixed with the polycarbonate to create a plastic-degrading toxic mixture. These results were verified by simply putting a piece of polycarbonate and the lubricant in a plastic bag. This test resulted in some seriously messed up plastic. Only some of the bearings E3D used caused this problem, a lesson for everyone to keep track of your supply chain and keep records of what parts went into products when.

The short-term fix for this problem is to replace the bearing in the Titan with IGUS solid polymer bushings. These bushings don’t need lubricant, and therefore are incapable of killing the polycarbonate shell. There are downsides to this solution, namely that the bushings need to be manufactured, and cause a slight increase in friction reducing the capability of the ‘pancake’ steppers E3D is using with this extruder.

The long-term solution for this problem is to move back to proper bearings, but changing the formulation of the polycarbonate part to something more chemical resistant. E3D settled on a polymer called Tritan from Eastman, a plastic with similar mechanical properties, but one that is much more chemically resistant. This does require a bit more up-front work than machining out a few bearings, but once E3D gets their Tritan parts in production, they will be able to move back to proper bearings with the right lubrication.

While this isn’t a story of exploding smartphones or other disastrous engineering failures, it is a great example of how your entire supply chain goes into making a product, and how one small change can ruin an entire product. This is real engineering right here, and we’re glad E3D finally figured out what was going on with those broken Titan extruders.