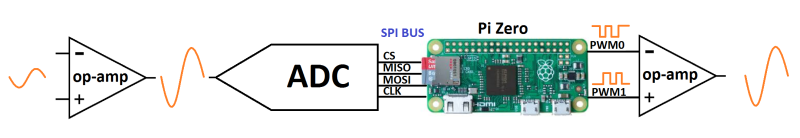

The Raspberry Pi is an incredibly versatile computing platform, particularly when it comes to embedded applications. They’re used in all kinds of security and monitoring projects to take still shots over time, or record video footage for later review. It’s remarkably easy to do, and there’s a wide variety of tools available to get the job done.

However, if you need live video with as little latency as possible, things get more difficult. I was building a remotely controlled vehicle that uses the cellular data network for communication. Minimizing latency was key to making the vehicle easy to drive. Thus I set sail for the nearest search engine and begun researching my problem.

My first approach to the challenge was the venerable VLC Media Player. Initial experiments were sadly fraught with issues. Getting the software to recognize the webcam plugged into my Pi Zero took forever, and when I did get eventually get the stream up and running, it was far too laggy to be useful. Streaming over WiFi and waving my hands in front of the camera showed I had a delay of at least two or three seconds. While I could have possibly optimized it further, I decided to move on and try to find something a little more lightweight.

Continue reading “Video Streaming Like Your Raspberry Pi Depended On It”

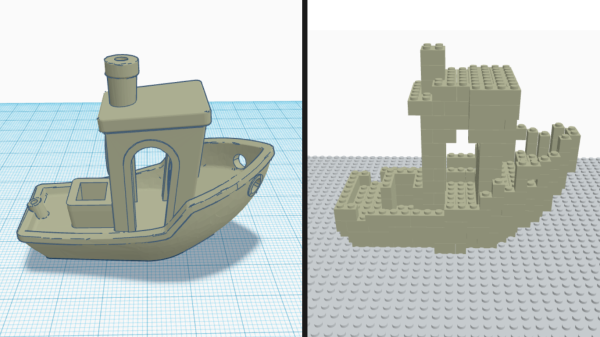

[Andrew Sink] made a

[Andrew Sink] made a

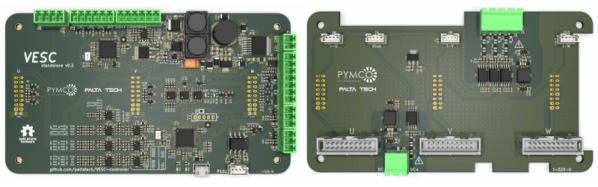

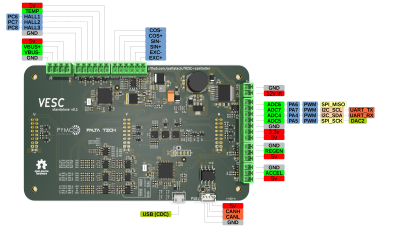

While [Vedder]’s controller is aimed at low power applications such as skate board motors, [Marcos]’s version amps it up several notches. It uses 600 V 600 A IGBT modules and 460 A current sensors capable of powering BLDC motors up to 150 kW. Since the control logic is seperated from the gate drivers and IGBT’s, it’s possible to adapt it for high power applications. All design files are available on the

While [Vedder]’s controller is aimed at low power applications such as skate board motors, [Marcos]’s version amps it up several notches. It uses 600 V 600 A IGBT modules and 460 A current sensors capable of powering BLDC motors up to 150 kW. Since the control logic is seperated from the gate drivers and IGBT’s, it’s possible to adapt it for high power applications. All design files are available on the