Right now, I’m at Shmoocon, and it’s living up to all expectations. That’s a tall order — last year, the breakout talk was from [Travis Goodspeed] on his efforts to reverse engineer the firmware for a cheap Chinese radio. Four people in the room for that talk last year bought the radio on Amazon, and now there’s a legitimate open source project dedicated to building firmware and tools to support this radio.

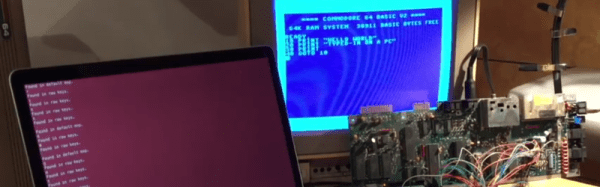

Now that [Travis] has a few compatriots working on firmware for this radio, he has the same challenges as any other team. The project needs unit tests, and this isn’t easy to do when all the code is locked up inside a radio. Instead of setting up an entire development platform based around a cheap radio, [Travis] came up with a toolchain that’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Instead of reverse engineering the firmware for this radio, he’s simply emulating the ARM firmware on the desktop. Development is quick and easy, and he has the live demos to prove it.

Now that [Travis] has a few compatriots working on firmware for this radio, he has the same challenges as any other team. The project needs unit tests, and this isn’t easy to do when all the code is locked up inside a radio. Instead of setting up an entire development platform based around a cheap radio, [Travis] came up with a toolchain that’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen. Instead of reverse engineering the firmware for this radio, he’s simply emulating the ARM firmware on the desktop. Development is quick and easy, and he has the live demos to prove it.

The heart of the Tytera radio in question is an STM32F405. This is a pretty common part, and thanks to [Travis]’ work last year, he has all the firmware that ships on this radio. This doesn’t mean he has access to all the radio’s capabilities, though; there’s a black box in the code somewhere that translates .wav files to radio packets and back again. Open sourcing this would usually mean reverse engineering, but [Travis] had a better idea.

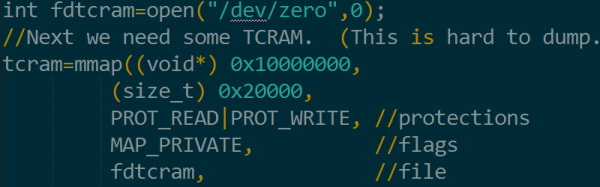

Instead of reverse engineering the entire radio, [Travis] is using QEMU to emulate an ARM microcontroller on his desktop, run the relevant code, and completely ignore any actual reverse engineering. Since this radio is already jailbroken and the community has a pretty good idea of where all the functions and subroutines are in the firmware, the most difficult part of pulling this trick off is setting up QEMU.

As a proof of concept, [Travis] downloaded raw AMBE packets from the radio to his laptop. These were then sent through the emulated radio, producing raw audio that was then converted into a .wav file. Effectively, a black box in this radio was emulated, which means [Travis] doesn’t need to know how the black box works.

All the code for this weird emulation / unit test, as well as everything the community has released for this radio is available on the GitHub. A lot of work has gone into the jailbreaking, reverse engineering, and emulation efforts here, making this radio somewhat ironically one of the most open radios you can buy.