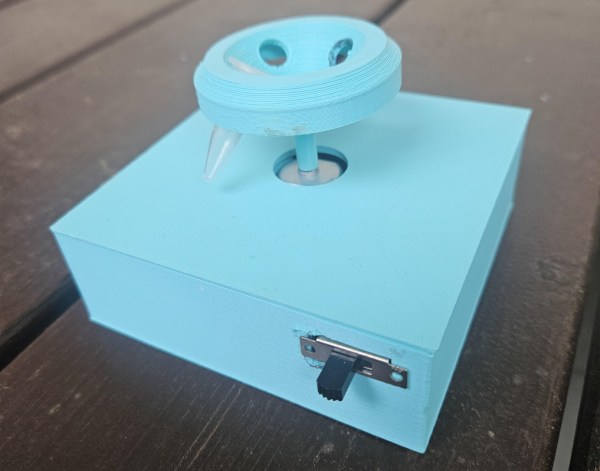

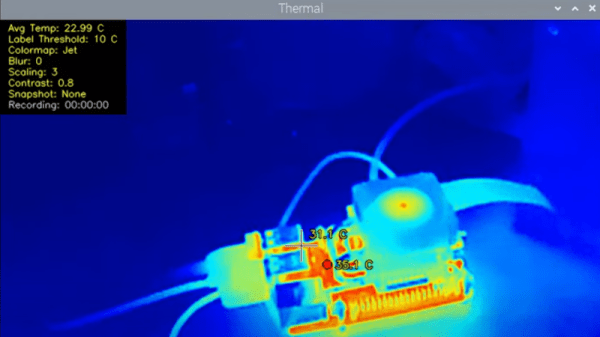

Debugging a Raspberry Pi Pico is straightforward enough; it simply involves hooking up something up to the USB and SWD pins. [Mark Stevens] whipped up the PicoDebugger to make this job easier than ever before.

The Raspberry Pi Foundation developed the Picoprobe system to allow a RP2040 to act as a USB to SWD and UART bridge for debugging another Pico or RP2040. The problem is that hooking it up time and time again can be fussy and frustrating.

To get around this, [Mark] whipped up the PicoDebugger board, which directly connects most of the important pins for you. Drop a Pico into the “Target” slot, and you can hook up the PicoDebugger to its UART lines with the flick of a DIP switch. The SWD pins can then also be connected via jumpers if so desired. It also features a 2×20-pin header to allow the target to be wired into other hardware as necessary.

It’s a neat project, and it certainly beats running a bird’s nest of jumper wires every time you want to debug a Pico project. Simply dropping a board in is much more desirable.

We’ve seen some other neat debug tools over the years, too. If you’ve got your own development productivity hacks in the works, don’t hesitate to let us know!