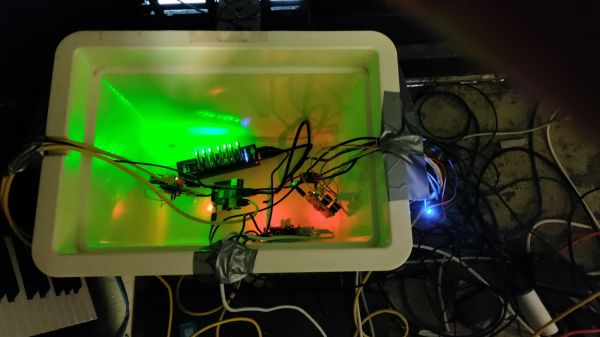

It seems there’s a service for everything, but sometimes you simply learn more by doing it yourself. If you haven’t enjoyed the somewhat anachronistic pleasures of running your own server and hosting your own darn website, well, today you’re in luck!

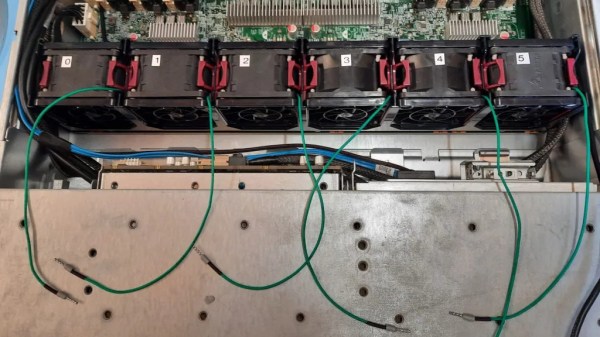

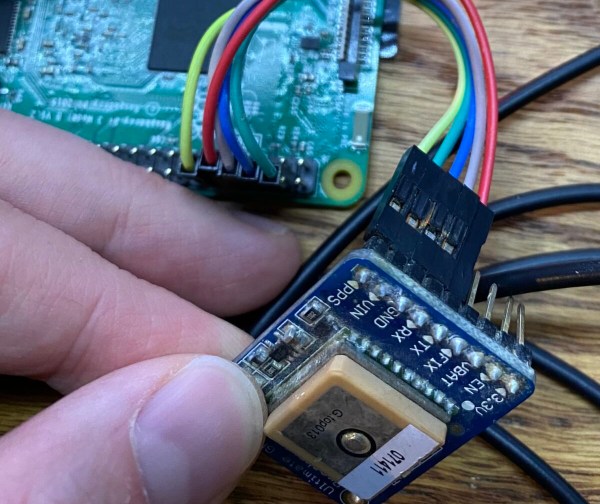

Yes, we’re going to take an old computer of some sort and turn it into a web server for hosting all of your projects at home. You could just as easily use a Raspberry Pi –even a Zero W would work — or really anything that’ll run Linux, but be aware that not all computing platforms are created equally as we’ll discuss shortly.

Yes, we’re going to roll our own in this article series. There are a lot of moving parts, so we’re going to have to cover a lot of material. Don’t worry- it’s not incredibly complicated. And you don’t have to do things the way we say. There’s flexibility at every turn, and you’re encouraged to forge your own path. That’s part of the fun!

Note: For the sake of space we’re going to skip over some of the most basic details such as installing Linux and focus on those that have the greatest impact on the project. This article gives a high level overview of what it takes to host your project website at home. It intentionally glosses over the deeper details and makes some necessary assumptions.

Continue reading “Run Your Own Server For Fun (and Zero Profit)”