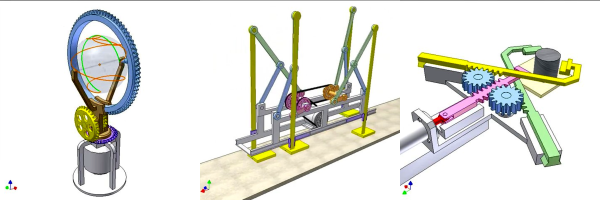

What can you do when you have a nice CNC machine, but build beautiful things like this 3-axis gimbal? We covered some of [Gal]’s work before, and he does not subscribe to the idea that hacks should look like hacks. If you’re going to spend hours and hours on something, why not make it better looking than anything you could buy off-the-shelf.

The camera is held stationary with three hollow shaft gimbal motors with low cogging. We weren’t aware of hollow shaft motors, but can think of lots of sensor mounts where such a motor could be used to make very compact and smooth sensor mounts instead of the usual hobby servo configuration. The brains are an off-the-shelf gimbal controller. The gimbal has a DB9 port at the back which handles charging of the internal LiPo batteries as well as giving him a place to input R/C signals for manual control.

The case is made from CNC’d wood and aluminum. There are lots of nice touches. For example, he added two buttons so he could fine tune the pitch of the gimbal. Each button is individually engraved with an up/down arrow.

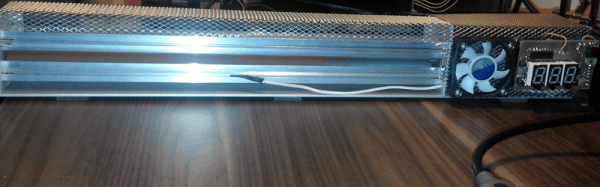

[Gal] reverse engineered the connector on Garmin action camera he’s using so he can keep it powered, stream video, or add an external mic. Next he built a custom 5.8Ghz video transmitter based on a Boscam module. The transmitter connects to the DB9 charging port on the gimbal.

It’s very cool when someone builds something for themselves that’s far beyond anything they could buy. A few videos of it in operation after the break.

Continue reading “Very Pretty Gimbal With Long Feature List”